Lorraine Julien | Apr 10, 2013

by Lorraine Julien

Butternuts (Juglans cinerea) occur in eastern North America, ranging from the southern states, west to Iowa and Missouri, north to southern Ontario and Quebec and east to the New England states. In Ontario it is found throughout southwestern Ontario north to the Bruce Peninsula and the edges of the Precambrian shield. Butternuts grow quickly to about 75 feet high but are short-lived for a tree, seldom living more than 75 years.

There are a number of these pretty trees along the road that I live but you can see that many of them have already died. Butternuts (or White Walnuts) are members of the Walnut family, which includes Black Walnut - the other native walnut in Ontario. Both produce edible nuts in the fall and both have roots that secrete something called juglone, a chemical that can kill other plants growing nearby. I’ve seen firsthand how almost nothing else will grow near this tree.

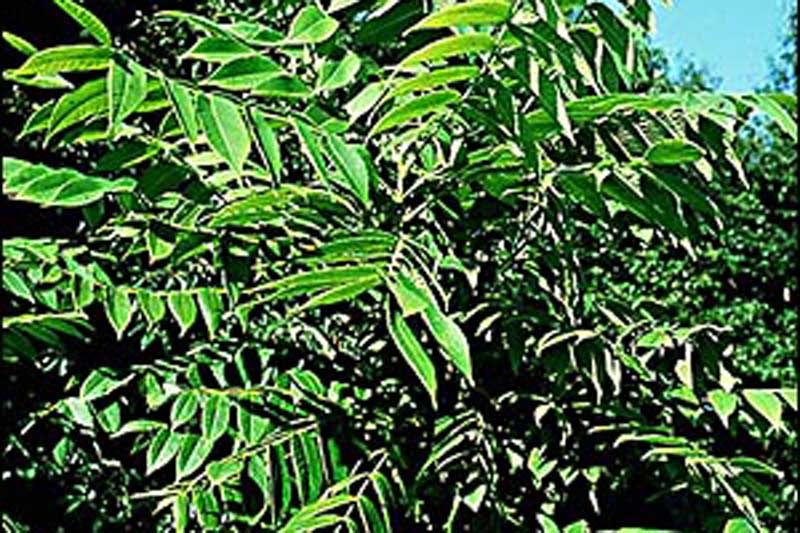

Both types of walnuts have similar compound leaves. The Butternut has 11-17 lance-shaped, sharp-pointed leaflets borne in pairs on a sturdy, hairy stem. Leaflets are 2-4” long with fine teeth along the edge. The bark is ash grey and very furrowed with broad, intersecting ridges.

Butternuts are found in low density scattered in and around forested areas. Originally their numbers declined as forests were cleared many years ago. Now, disease threatens to decimate them entirely. It’s a real shame that another of our native trees is in such rapid decline.

The Butternut is mostly valued for its fruit or nuts rather than its lumber. Nuts are in the shape and size of small lemons whereas Black Walnut fruit is perfectly round but similar in size. The nuts are eaten by humans and by many animals. Now before you go searching for white or black walnuts this fall, keep in mind that these are “tough nuts to crack”! To extract the tasty kernel, the outer husk must be crushed (some people suggest driving over them with a car!) Then the nut must be peeled which is difficult to do without staining your hands. The rock-like inner shell yields only to repeated hammer blows. Walnuts that are available in stores are hybrids from the English walnut and are much easier to crack since their thick husks are removed before the nuts are shipped.

Many years ago, Butternut fruit was used in baking and making maple-butternut candies – I don’t know if that is true today. Native Americans used to boil the nuts to release the oil in them. They’d scoop it off the top of the water and use it as we use butter – hence the name “butternut”. Butternut wood is light in weight, extremely rot resistant but much softer than Black Walnut wood. It is often used to make furniture and is a favourite of woodcarvers.

Butternut bark has some medicinal uses: it has mild cathartic or healing properties. Hundreds of years ago, an extract was made from the inner bark of the Butternut in an attempt to prevent smallpox and to treat dysentery and other stomach and intestinal problems.

Butternut bark and nut rinds were once often used to dye cloth to colours between light yellow and dark brown. To produce the darker colours, the bark is boiled to concentrate the colour. These natural dyes were never used commercially but were used to dye homespun cloth.

I’ve heard a lot recently about Butternut trees and how their numbers are dwindling mainly due to a fungal disease called Butternut Canker. The disease was first discovered in 1991 in Ontario and has been spreading rapidly ever since. It’s thought that the disease was spread accidentally when infected plants were imported from overseas. Once the fungus starts, it can kill a tree within just a few years. The fungus enters the bark through cracks or wounds and multiplies rapidly making sunken cankers that expand and girdle the branch or trunk, killing everything above the canker. Fungus spores can be transported in wet weather for miles, quickly spreading the disease. In the U.S. southern states such as Tennessee, the disease has already killed about 90% of the Butternuts. Surveys in eastern Ontario show that most trees are now infected, and perhaps one-third have died.

Today, protection is provided to the Butternut under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 which prohibits anyone from doing harm to these trees. Though some grow in provincial and national parks where they are protected from cutting, most grow on private lands. There is no known cure for the canker disease or any effective technique to slow or prevent the spread of the disease. Some work is being done to produce hybrids that may be resistant to the Butternut Canker and also to gather seeds from strong, healthy trees.

The Rideau Valley Conservation Authority is working with the Forest Gene Conservation Association and the Ontario Butternut Recovery Team to build a strong Butternut recovery program across Ontario. Many conservation authorities and stewardship councils as well as local landowners have joined in the fight to save this tree from complete decimation. The Ottawa Stewardship Council is assisting RVCA in looking for properties with mature Butternut trees to assess and/or for properties for planting young Butternut seedlings germinated from selected stock. If you are interested in participating in this program as a landowner, you can check out the website for information at www.ottawastewardship.org or by email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Please feel free to report any observations to Lorraine Julien at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or Steve Blight at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

More Stories

- Latest CUPW Job Action Stops Postal Delivery Of The Frontenac News Forcing Alternate Plans

- Opponents of Barbers Lake Gravel Pit Pack Ag Hall in McDonalds Corners

- Bobsleigh Olympian Jay Dearborn At Mikes Pizza In Sydenham

- The Loins Club Of and O'Lakes Roar

- North Frontenac Back Roads Studio Tour - September 27 and 28

- Sunday Market Vendors Give Back

- George Street Work As Town Hall Renovation Nears Completion

- One Way Street Plan Hits A Dead End - Central Frontenac Council, September 9

- Global Gardening

- No Winner Yet in Catch The Ace But Fundraising Target Met