Jeff Green | Feb 28, 2018

In order to explain the relevance of the corridor of territory that links two of the larges wilderness parks in the Eastern Seabord, Adirondack Park in New York State and Algonquin Park in Ontario, the story of Alice the Moose always comes up. Alice was first identified in Rochester in New York State, and later on she turned up in Algonquin Park.

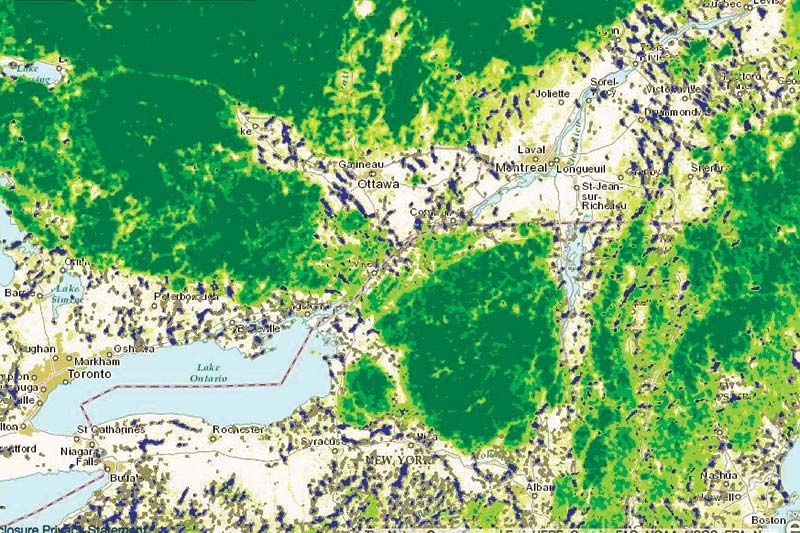

Her journey included hopping from island to island in the Thousand Islands on the St. Lawrence River. She then traversed along a corridor of lakes and wetlands in Eastern Ontario of which Frontenac Park in South Frontenac and Frontenac Parklands in North Frontenac make up the western edge, and over the Madawaska river and on to the park. The corridor through which Alive travelled encompasses an area of ecological diversity that both extends the range of some species, and, like Alice, allows others to migrate from one rich habitat to another.

With the stress of climate change now upon us the resulting change in habitat, the corridor can be a crucial means for animals to adapt to changes.

A2A, the Algonquin to Adirondack Collaborative, is a small, partnership based organisation devoted to exploring and maintaining the vibrancy of this corridor.

David Miller is the Executive Director of A2A, and he made a presentation at the Annual General Meeting of the Friends of Frontenac Park last weekend about A2A.

The Frontenac Arch of the Canadian Shield plays a crucial role in creating the varied landscapes that make the corridor function, and A2A works on mapping the area, helping provide passage over some of the major hurdles in the corridor such as the 401 Highway, the Thousand Islands Parkway and Hwy. 2, and does a lot of work publicizing the corridor.

“One thing we do is create a great summer research job for a student, walking along the highway counting squashed critters. An average of 70 vertebrates are killed each day, and the information gathered by knowing where those animals cross the road, helps us work with the MTO [Ministry of Transportation] to figure out where to locate fences, where to re-do culverts to let specific species through, etc.” he said.

“There is stuff we can do when we have the correct information, relatively simple things that can make a difference, and then there are more complicated things,” he said.

One of the more complicated things is to impress on planning bodies such as municipalities that a level of landscape planning, looking at the broad regions ecological function, needs to be incorporated into local planning around proposed developments in order to keep the corridor functioning.

“One advantage we have is that there are no larger cities in the corridor, so development is not likely to create a massive impediment to migration,” he said.

A2A has been researching a number of types of plans, including municipal natural heritage strategies, park and watershed plans, and land trust/conservancy and nature conservancy plans, in order to develop a lens to provide to municipal planners so that landscape planning can begin to be integrated into land use planning.

“Land use planning tends to be reactive,” Miller said, “a development is proposed and the planning department reacts, and in that context making sure a larger perspective is taken into account is difficult to achieve.”

A2A has also done a major mapping project to create better awareness of the corridor.

Finally, an A2A trail, which makes use of existing trails and the occasional back road, has been identified.

Last summer naturalists from Algonquin Park and Adirondack Park set out from their own parks at the same time and they eventually met up in the middle point of the 650 kilometre trail.

“What the trail demonstrates is not only the beauty of the landscape but the cultural values as well, the small towns and rural properties along the route and the people whom live in them,” Miller said.

For further information, go to A2Acollaborative.org.

More Stories

- Latest CUPW Job Action Stops Postal Delivery Of The Frontenac News Forcing Alternate Plans

- Opponents of Barbers Lake Gravel Pit Pack Ag Hall in McDonalds Corners

- Bobsleigh Olympian Jay Dearborn At Mikes Pizza In Sydenham

- The Loins Club Of and O'Lakes Roar

- North Frontenac Back Roads Studio Tour - September 27 and 28

- Sunday Market Vendors Give Back

- George Street Work As Town Hall Renovation Nears Completion

- One Way Street Plan Hits A Dead End - Central Frontenac Council, September 9

- Global Gardening

- No Winner Yet in Catch The Ace But Fundraising Target Met