Steve Blight | Jun 01, 2016

Ticks and Lyme disease have been in the news a lot recently. While there is currently much welcome discussion about effective testing and treatments, one thing that needs no debate is that black-legged ticks and Lyme disease are here in the Land O’Lakes. As our climate warms and winters become less severe (remember the balmy +17 degrees last Christmas Eve?), the black-legged tick has been gradually moving north from its principal range in the United States and has brought Lyme disease with it. Both are now permanent residents in our area.

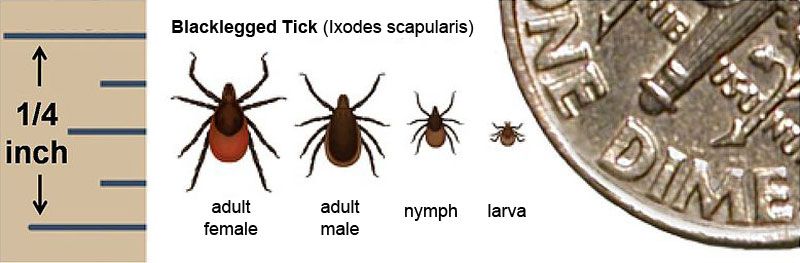

Ticks are arachnids, members of the same family as spiders, mites and scorpions. Adult black-legged ticks (also known as deer ticks) are dark, about the size and shape of a sesame seed, and have eight legs – a feature that helps to quickly distinguish them from six-legged insects. Deer ticks have a complex two-year life cycle during which time they pass through three stages: larva, nymph, and adult. The tick must take a blood meal at each stage before maturing to the next. Adult tick females latch onto a host and drink its blood for four to five days. In late spring the female lays several hundred to a few thousand eggs on the ground in clusters. In our area, the adult ticks are more numerous in early to mid-spring and then again in mid-fall. Immature ticks, known as nymphs, are much smaller than adults (about the size of a poppy seed) and actively search for a blood meal in May through July.

About six or seven years ago, we had our first experience with ticks when we found a funny little bump on our dog’s neck. It was October, and she had spent the previous weekend chasing chipmunks at our cottage on Bobs Lake. By mid-week the “bump” had become the size of a small dried bean. We looked at it closely and realized that it was no ordinary bump – it was a partially engorged tick. I found some tweezers and pulled it off, being careful to grasp the tick right by the dog’s skin to ensure I didn’t leave the tick’s mouthparts attached to the dog. Legs wiggling in protest, I disposed of the tick in such a way that that this particular individual was not going to bother anyone ever again. Period.

Later that same fall, I found a tick on my neck after spending a few hours in the bush, and since then every spring and fall my wife and I find a few of the little beggars crawling around on either our clothes or on our skin. We used to find 3 or 4 ticks on our dog every week, but since we began treating her with a vet-prescribed anti-tick medication we rarely see any on her.

If being bitten was the only nasty thing about this critter, it wouldn’t be so bad. After all, there are gazillions of biting flies in this area. Unfortunately, as mentioned earlier, deer ticks are the principal way that Lyme disease is transmitted to people. Known as a “vector” in the bug business, ticks often have the species of bacteria that causes Lyme disease living in their gut. They pass on the bacteria to mice and deer that they normally feed on, giving other ticks the opportunity to become infected when they feed on the infected mammal. And so on. All three stages of ticks can pass on Lyme disease, but according to one reputable source, the nymph stage is responsible for the majority of human cases of Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is named after the town of Lyme, Connecticut, where a number of cases were identified in 1975. Early symptoms may include fever, headache, fatigue, depression and a characteristic circular red skin rash, described by some as looking like a bull’s eye or a target. Left untreated, later symptoms may involve the joints, heart, and central nervous system. The good news about Lyme disease is that the probability is extremely low that a tick passes on the bacteria to a person if the tick is found and removed within the first 24 hours of attachment to a person. The other good news is that in the large majority of cases the infection and its symptoms are eliminated by antibiotics, especially if the illness is treated early. Unfortunately there is currently no vaccine available for Lyme disease, but there is much scientific work going on right now aimed at developing an effective one.

Not surprisingly, the Internet is jam-packed with information to help people deal with ticks and Lyme disease. The best advice I have found is summarized below, and begins with prevention.

-

Wear light coloured, long-sleeved shirts and pants when working in the woods or brushy areas. The light colour makes the ticks more visible and thus easier to find and remove.

-

Some people find it practical to have a separate set of outdoor clothing that they change into and out of outside the main living area of the house (e.g. a garage, porch or shed).

-

“Death by dryer” works too. Putting your clothes in the dryer on high for five minutes will kill the ticks.

-

Tuck pants into socks. I know it looks goofy, but it prevents the ticks from getting under pant legs. Some people wear rubber boots, but they can get hot in the summer.

-

Use insect repellent on sleeves, cuffs and socks. Repellents containing DEET are known to be effective.

-

Shower after spending time outside and get into the habit of conducting full-body checks, using mirrors and if you so desire, the help of a willing partner. Remember, removing ticks before 24 hours is key.

-

Use tweezers or one of the specially-designed tick removers available at many public health units to carefully pull off any embedded ticks, being careful to grasp the tick very close to the skin and pull it out, mouth parts and all. Wash the site thoroughly and treat it with alcohol.

-

If you do remove an embedded tick from your skin, watch the site carefully for any signs of an expanding red rash. A small, itchy reddish bump (like a long-lasting mosquito bite) at the site is normal, but a large spreading rash is not.

-

If you have any doubts at all, contact your local public health authority or consult with your medical care provider. The tick I removed from my neck was sent to be tested for Lyme disease, and fortunately it came back negative.

For people who are interested in reading more, the best reference website I have found is available at this link http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/. There is plenty of good information available on Canadian websites (e.g. Health Canada, Government of Ontario) but the information on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website seems the most comprehensive and authoritative.

Ticks are here for good, so the best defense is a good offence. By learning to recognize them, taking a few steps to avoid them, and knowing what to do when you find one, we can minimize the risks. For my part, I’m determined not to let ticks spoil my time in the woods!

Please send your observations to Lorraine Julien at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or Steve Blight at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

More Stories

- Dry Conditions Spark Fires in Fields and Forests

- 143rd Maberly Fair

- Local Seniors Medal at OSGA 55+ Provincial Games

- Seventh Town Serenades Sharbot Lake

- Brass Point Bridge Closure Leaves Commuters Behind

- Wild Art Walk Call For Submissions

- Three Dwelling Limit Coming For Lots in North Frontenac

- Wildfire in the 1000 block of Rutledge Road - Township Says Fire Now "Under Control"

- Verona and Sydenham Ballpayers Win National Championship With Kingston Colts

- Sweet Music and Some hard Truths At Blue Skies MusicFestival