Jan 11, 2023

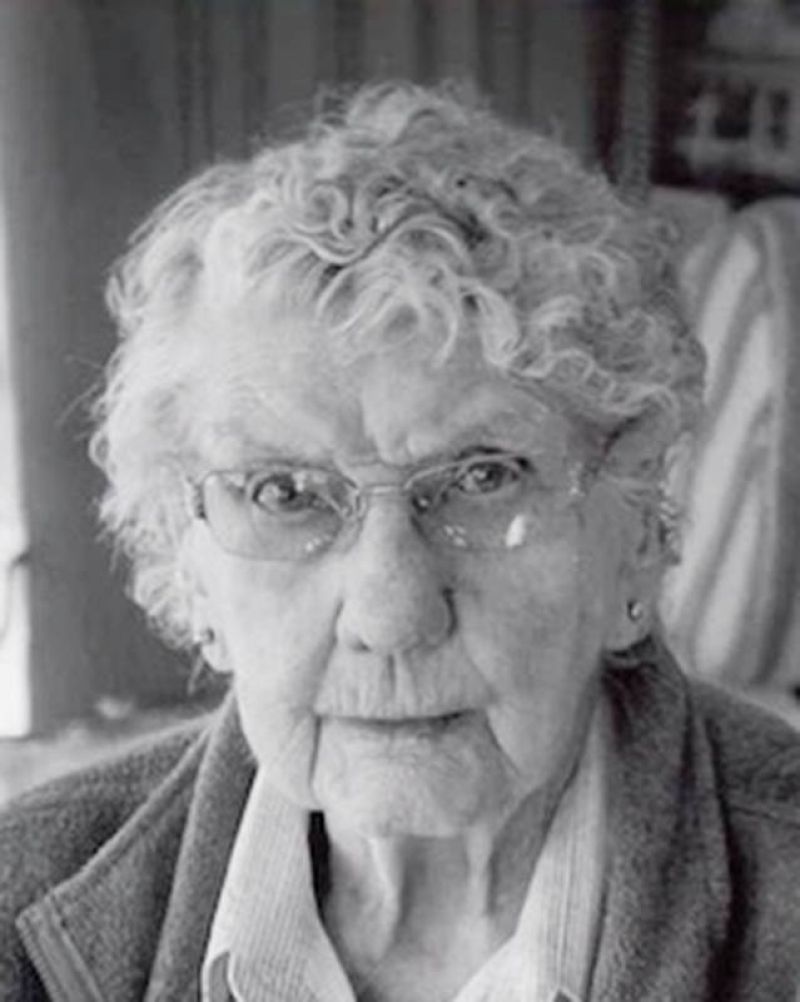

(As reported elsewhere in the paper, Lee Anna White died last week, just before here 108th birthday.)

Back in 2015, when she was not yet 100, we interviewed her as part of our Frontenac County 150th anniversary coverage. That article is reprinted below in her memory)

It was in late August that I went to interview Lee-Anne White at her home on Road 506 at Fernleigh, which at one time was a full-fledged hamlet with a post office, a store and a school, but is now only a clutch of houses around a crossroad.

I was accompanied by Jesse Mills, the videographer for the Frontenac County 150th anniversary project, and when we arrived Lee-Anne had a bandage on her leg and was limping when she opened the door for us.

“The nurse was just here this morning,” she said, “to change the dressing on my leg.”

She had hurt her leg by dropping a piece of wood on it as she was feeding the box stove in her basement to take off the morning chill a few days earlier. But though her leg was slowing her down, she still had a basin overflowing with bread dough in the kitchen and was de-frosting five pounds of ground beef to make meatballs for a family reunion that was coming up on the weekend.

Aside from her leg, something else was bothering her. Her car, a 2010 model, was in need of some work.

“They tell me that I don't drive it enough. That's why the linkage needs to be fixed and it needs new tires. I haven't told my son yet but I think I'll trade it in on a new one rather than bother with it,” she said.

Lee-Anne Kelford was born at Ompah on January 9, 1915, and this week she turns 100. She remembers the kinds of efforts that were required to survive on the Canadian shield farmland in the days before electricity, cars and other modern conveniences. What money her family made came from her father shoeing horses or milling wood, but most of the food they ate they had either grown, gathered or slaughtered from their own herds of cattle, sheep and pigs. For chairs they used burlap bags stuffed with straw or hay. They went barefoot in the summer and in the winter wore gumboots with homespun yarn straight off the sheep wrapped around them for warmth. When she was coming home from school with her brothers and sisters her mother would meet them with baskets and they had to fill the baskets with wild strawberries or raspberries on the way home. In the spring they would catch hundreds of suckers and salt them for winter eating. In the summer they picked blueberries and apples, worked in the garden and helped harvest hay and grain.

While the large 17-member Kelford family, seven brothers and seven sisters, father and mother and hard-bitten grandmother Jane Kelford, never had a lot of money, they were certainly not the poorest family around

“We were better off than those that were further down the line, I'd say. We always had enough to eat; we had cows and sheep and a big garden and a root cellar and mother was always baking biscuits or something, so we had no complaints,” said Lee Anne.

She still talks about her father's capacity to build things and make things work on their property. Although he could not read or write, he managed to build a steam-powered sawmill, a smithy and whatever the family needed to get by.

However, he may have taken on a bit much when it came to orthopedics.

When Lee-Anne was seven years old she fell out of an apple tree in an old orchard where she was picking apples with her mother. Of course there was no 911 to call. As she recalls it, she had driven the horse-drawn wagon to the orchard while her mother held her baby sister Elsie. Since her arm was broken and the bone was sticking out, her mother popped Elsie on Lee-Anne's lap and tied the baby to her so she wouldn't fall off. Her mother then drove home.

When they got back to Lee-Anne's father's wood and smith shop back at Ompah, he looked at her arm quickly and decided it needed to be set.

So, “he took an old cedar block, about 6 inches long, that was lying around,” in Lee-Anne's words, cut it and augured out the centre, then cut it again and split it to fit her small arm. He put her arm in and tied it together snugly with string, forcing the bone back into place at the same time. The next day her brother Sam got into a fight with another brother, Wyman, and Sam's wrist ended up being broken. Their father set that wrist as well.

The children then had to immerse their arms in a barrel of ice water repeatedly over the next two days, presumably to keep the swelling down. The treatment was successful in both cases - to a point. Lee-Anne was able to use her arm afterwards, but could not raise it all the way up to the top of her head, and her brother developed growths on his wrist.

At the time and to this day, after 93 years have passed, Lee White supports everything her father did that day.

“A neighbour said he should take us to a doctor but there was no doctor close by and we didn't have money to pay for a doctor anyway,” she said.

Her father lived a long life as well. He died at the age of 97 in 1977.

When Lee-Anne was older she took a job at a new lodge on Kashwakamak Lake that was opened up by an Ahr family from the United States. The lodge, which became known as the Fernleigh Lodge, is open to this day. She worked there for seven years, cooking and cleaning for over 100 guests at a time, and in the winters she worked at the Trout Lake Hotel in Ompah.

It was at Fernleigh Lodge that she met her husband, Melvin White, who was a guide in the summer and fall and trapped in the winter time. Melvin was from Plevna, and although he ran away from home at age 16, when the couple got married, Lee-Anne ended up living at Melvin's taking care of Melvin's parents and their farm for at least one winter during the 1930s, when she wasn't drawn back to Ompah to help her own family get by.

Eventually, Melvin was given a one acre piece of land on what is now Road 506 and the Whites built a 23 x 14 foot shack for themselves. Afterwards they built the house where Lee-Anne still lives on the same property (Melvin died in 2009).

“We scratched I tell you, but we never borrowed a cent in our lives. When we were building our house, with help from his half brother and uncle, I said to Melvin I'd rather eat one meal a day than go into debt.”

The couple had three sons, George, Andy and Danny. Lee-Anne ended up taking a job drawing mail from Fernleigh to Cloyne, a job she kept for 38 years.

At her 100th birthday party at the Clar-Mill Hall last Saturday, her sons were all there, as were her grandchildren, daughters-in-law, nieces and nephews and long-time friends. Sitting at the front with her, among the certificates from the governments of Ontario and Canada and one from Queen Elizabeth, was her aunt Agnes, who is 101 and still lives near Ompah. When it came time to take a family picture, both women pulled themselves out of their chairs, even though Agnes recently had an operation, and they walked over to be in the picture.

Back in the summer, we left some of our equipment at Lee-Anne's house when we recorded the interview. When I dropped back to collect it a few days later, I found her leaning into the back seat of her car, reaching over, with a vacuum cleaner going.

“I'm tying to get it ready for sale,” she said.

One thing that Lee White did not do was drive to her own 100th birthday party. The weather was pretty stormy that day so she took a ride from one of her sons. But she insisted that they take her brand new red truck, which they parked just out from the front door of the hall.

It's a nice looking truck - paid in full, to be sure.

There is a video below, and there is also a second video on Youyube. Click to broken arm video the clip tells the whole story of Lee-Anne's broken arm.

More Stories

- Dry Conditions Spark Fires in Fields and Forests

- 143rd Maberly Fair

- Local Seniors Medal at OSGA 55+ Provincial Games

- Seventh Town Serenades Sharbot Lake

- Brass Point Bridge Closure Leaves Commuters Behind

- Wild Art Walk Call For Submissions

- Three Dwelling Limit Coming For Lots in North Frontenac

- Wildfire in the 1000 block of Rutledge Road - Township Says Fire Now "Under Control"

- Verona and Sydenham Ballpayers Win National Championship With Kingston Colts

- Sweet Music and Some hard Truths At Blue Skies MusicFestival