Jeff Green | Aug 02, 2017

It was a dream of trail proponents to use the old K&P rail line to create a trail that would connect the east-west trans Canada Trail with the Cataraqui and Rideau Trails and ensure that the trans-Canada Trail takes a detour through the Frontenac County trail system. In order to make that happen the K&P trail needed to be complated between the junctions in Sharbot Lake and Harrowsmith, and Frontenac County has been working on that for 10 years.

The alternative would have been for the Trans Canada to flow along Hwy 7 directly between Ottawa and Peterborough, bypassing the Rideau and Cat Trails, Frontenac Park and the varied landscape of the Frontenac Spur and the Frontenac Arch Biosphere.

The dream is about to become a reality and that reality will be celebrated on August 26, Canada 150 trail day, which is being sponsored by the Federal government to the tune of $1 million.

Unfortunately, the K&P trail between Sharbot Lake and Harrowsmith will not be finished by August. The complicated northern section between Tichborne and Sharbot Lake is underway, and sections are done, but it is not going to be complete by August 26.

In a way, the trail being officially launched without actually being in place fits well with the history of the K&P Railroad itself. It was an idea that had its supporters, even if the money was not in place and the details were not worked out back in the 1875 when it opened. And of course, while the trail top Sharbot Lake will not be complete on opening day, it will be completed soon, while the K&P (which stands for Kingston to Pembroke) never did make it that far. It only ever extended as far as Renfrew.

In his new book, The First Spike, Steven Manders has provided some new information about the building and management of the K&P line, and it’s relation to an over-estimation of the value of iron mines at Iron Junction, present day Godfrey. Manders did some traditional research. and he also interviewed elders such as Don Lee and Les McGowan and got into is canoe to look for signs of the old mines on 13 Island and other local lakes.

As he says in his book, you would never know from looking now at what appears to be an entrenched rural cottage region, that there dozens of small mines, kilns, canals, barges, and much more in the region as recently as 100 years ago. Manders has found remnants, bits of metal, old spikes, wheels, etc in his many trips to the area looking for evidence of past history.

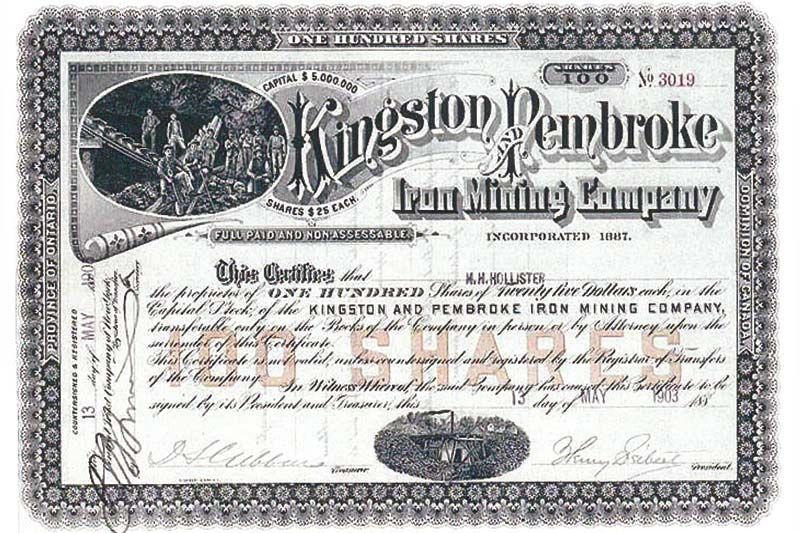

In the early days of the K&P, spur lines were built to bring iron ore, feldspar and other minerals to Bedford Station at what was then known as Iron Junction where the heavy loads were transferred to trains on the K&P for transport to Kingston and the US. It was this resource that was the impetus for the construction of the K&P, and US based industrialists were among the early investors in the railroad. In 1884 the K&P had its best year. turning a profit of over $20,000. Within ten years, with the iron ore proving harder to access the K&P had become a money loser, to the tune of $100,000 or more per year (about $2.7 million in 2017 dollars). The railroad went into receivership until 1899, and then began to be swallowed by by Canadian Pacific Railroad, a process that was completed in 1913 when the CPR took on a 999 year lease on the line and acquired all the assets. The book also includes information about the K&P iron mining company, which was unrelated to the railroad but shared some Directors and investors, suggesting that stock manipulation, or ‘mining the market’ as it is sometimes called, took place on a large scale, in the 1890’s and into the new century, and a man named Henry Siebert continued to sell certificates for the K&P mining company long after he had received reports that there was no viable iron resource left in the ground. Between 1896 and 1903, about $2.5 million in shares were sold (over $500 million in today’s dollars) in a company that was never destined to deliver anything to market.

The First Spike also looks in depth at some of the communities and stations as the line moved north, and images of villages such as Clarendon Station and others that show how active and populated they were when the rail line was a going concern.

The railroad was never sustainable as a passenger line, and indeed according to Steven Manders, the CPR was never really interested in the section of the line north of Tichborne, where the K&P and the main CPR line, which still exists as travellers along Road 38 are well aware.

As we all know, the K&P ceased operations entirely eventually and will soon be entirely transformed into an operational trail, ensuring a strong presence of the Trans-Canada Trail in Frontenac County, by the time the 2018 tourist season rolls around.

The K&P railroad cost about $3.5 million to build in the 1870’s, the equivalent of about $100 million in current dollars, and the cost to build the trail remains a bit of a mystery. It has taken years to build, and has been funded in part by Federal and Provincial trail grants as well as some municipal gas tax rebate money in the early years.

As even a cursory look at the First Spike reveals, the issues surrounding the development of the K&P trail, some of which have been revealed over the years in this paper, are nothing new to the K&P. It has always been an expensive proposition. As a trail, all it needs to do is attract a reasonable number of people to enjoy walking, riding, cycling, and sledding over it in order to be a success. The stakes are lower than they were back when investors expected to make their fortunes out of a doomed rail line. Still the expectation that the trail, combined with the opportunities for outdoor recreation and the efforts of some of the newer and more established entrepreneurs seeking to build a tourist economy, will bring benefits to Frontenac County residents over time.

More Stories

- September Closures for Northbrook And Sharbot Lake Beer Stores

- This "Doc Is Not In Anymore" After 54 Years

- Mazinaw Lake Swim Program Only Getting Stronger After 53 Years

- "Jack of Diamonds, Jack of Diamonds" but No Ace Of Spades Yet

- Sydenham Legion Presents ATV to Canada Day Raffle Winner

- Bathing in Blue Mindfulness: An Otter Lake Journey in Frontenac Park

- Central Frontenac Buys Used Pumper At Special Meeting

- 4th Annual Sharbot Lake Beach Bash

- Frontenac ATV Club Rallies For A Community Cause

- Harrowsmith Shadowdale Blooms: Kindness In Full Colour