Jeff Green | Dec 02, 2015

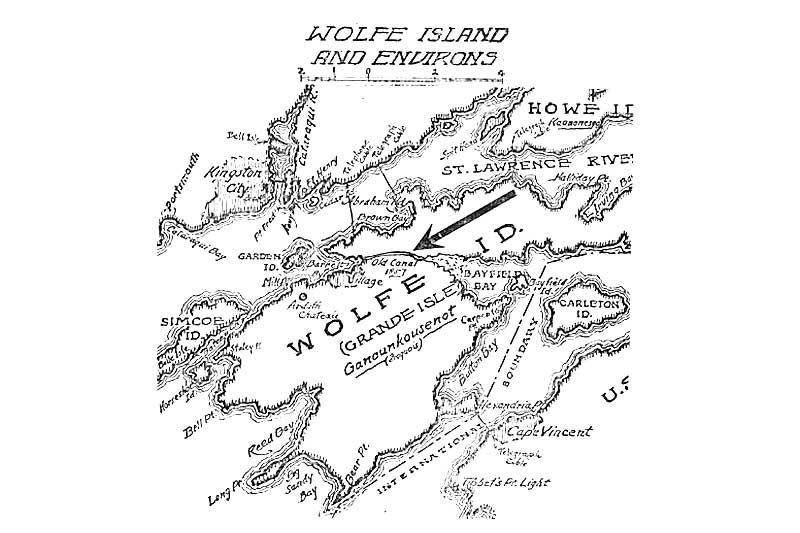

In 1973, Winston Cosgrove published a 60-page book on the history of Wolfe Island. Wolfe Island Past and Present outlines how the island came to be settled, how it remained in use by indigenous peoples as fall and winter fishing and hunting grounds until the middle of the 19th Century, and how the population peaked in the late 19th Century before beginning a long decline that has only recently been reversed.

The book is written in a kind of discreet manner that suggests its focus was more in the past than on what was then the present, and of course 40 years have passed since it was published. It contains, however, much information about how the island community developed from the late 17th until the 20th centuries.

In 1685, Robert Cavallier, Sieur de Lasalle, having been granted the Signeury of Fort Frontenac by King Louis the 14th ten years earlier, conferred ownership of what would become known as Wolfe Island on James Cauchois. It was the “first conveyance of any part of Ontario from one subject to another”.

The land remained in the Cauchois family for over 100 years, until it was sold in the early 1800s to David Alexander Grant and Patrick Langan for one shilling an acre. Grant had married the Baroness of Longeuil in 1785, and although the sale of the island to Grant and Langan severed all ties to the French monarchy it did establish the Baron of Longeuil as a major force on Wolfe Island.

In 1823, David Alexander's son, C.W. Grant, the 4th Baron of Longeuil, owned about 11,000 acres on the island. A similar amount was split among the three daughters of Patrick Langan. Two-sevenths of the land had been turned over to England's King George when the British overturned French rule in the entire region.

Grant sold off 100 acre lots starting in 1823, and settlement began in earnest. He also had a large house constructed near Marysville. The house, which was called Ardath Chateau, was known locally as the “The Old Castle”. It had 25 rooms, a dungeon, a carriage house and servants' quarters and was the “focal point for many years of life on the island”. In 1929 the house, which had been unoccupied for at least 15 years, was razed in a fire.

“Being a native born Islander, this writer recognises the staunch loyalty among the Islanders for one another and out of respect for this tradition, would prefer 'to let sleeping dogs lie' rather than delve further into the matter.” This suggests that Winston Cosgrove knew more about the fire than he was willing to say, and in all likelihood further information about what happened that dark night in 1929 is still carried by any number of Wolfe “Islanders”.

Although “The Old Castle” was certainly grand, the housing situation for Wolfe Island settlers in the early to mid 19th Century was more modest.

Fifteen settler families lived on the island in 1823, and this increased to 261 persons by 1826. The population grew steadily, peaking at 3,600 by 1861.

When the island was being settled in the 1820s and 30s “the typical house was a log cabin, 20 feet long by 16 feet wide, 6 logs high, with a shanty or sloping roof. Some had glass but most often the windows were only holes in the wall, which could be covered in the winter.”

During the 1850s, demand for lumber for D. D. Calvin's shipbuilding operation on nearby Garden Island led to a lumbering boom on Wolfe Island, and the boom ended when the trees were gone. The population began to dwindle at that point, and by the time Cosgrove's book was published in 1973, it was down to 1,200. It had dropped to 1142 by 2001, and the 2011 population survey lists Frontenac Islands (including Wolfe and Howe Island) at 1864. The current permanent resident population of Wolfe Islands, according to Wikipedia, is 1,400, although it is twice that or more in the summer (perhaps excluding this past summer due to the Ferry Fiasco of 2015).

Wolfe Island Past and Present contains a wealth of information about landmarks and renowned island residents. It explains how Marysville was named after Mary Hitchcock, who lived all of her 92 years on the island and was its first postmistress between 1845 and her death in 1877.

The General Wolfe Hotel, originally known as the Wolfe Island Hotel, was built in 1860. It was renamed the General Wolfe by the Greenwood brothers in 1955, and benefited from the results of a liquor referendum in 1957, which was won by “the wets”. The hotel remains an island landmark and a major part of the hospitality industry. It's 130-seat restaurant has won a number of provincial awards.

The final chapter of the book deals with a crucial subject, one that has been top of mind on the island this summer and was also the subject of a discussion and slide show on Wednesday, December 2, “Ice Travel” with Kaye Fawcett and Ken White, which was organised by the Wolfe Island Historical Society.

Throughout Frontenac County the history of road and railway construction is full of colour, hardship and a fair taint of corruption and scandal.

On Wolfe Island there is an added dimension - the water that separates the island from the mainland and the City of Kingston. It was 50 years ago, in 1965, that a year-round ferry service financed by the Province of Ontario was established on Wolfe Island.

Until then the ferry service ran only until freeze up, and during the winter an ice road was the way across.

In 1954 the winter was so warm that the ferry was only inactive for 2 days, but between 1955 and the onset of the year-round ferry in 1965, the range was 60 to 110 days, with an average of about 80 inactive days each winter.

Over the years, tragedies and near tragedies occurred on the ice on many occasions. One of the more famous events was the near drowning of entire families on Christmas Day in 1955.

The ferry was out of commission because of an early winter, but a tug boat, the Salvage Prince, waited at the edge of the ice at Barrett's Bay for families who had come to the island for Christmas Day and were returning to Kingston late in the afternoon. They were being drawn across the ice in a sleigh, but just before reaching the boat, the sleigh went through a wet spot in the ice, forcing a hurried and dangerous rescue, as children, adults and seniors, were luckily all pulled out of the freezing water back to the tug and a boat ride to Kingston. Some were taken to the hospital for observation. An account of the trip by Brian Johnson is available at thousandislandslife.com.

In the concluding pages of his book, Winston Cosgrove makes the argument that the economy of Wolfe Island will be doomed unless a bridge is built.

“In the past the economy of the island has been purely an agricultural one, with hunting and fishing and summer residents as minor items. Under this system the population has dwindled. The key to the problem is transportation. There is much beautiful undeveloped shoreline and land that is is well-suited for permanent homes but better ways are needed to get to and from the mainland if the community is to develop and grow. A ferry service is not efficient enough ... Meanwhile the Islanders who want a bridge must be content to await future developments while acting as guardians of a great land developed by pioneers, to whom all are indebted.”

Although Cosgrove's views may have had a lot of currency this past summer while the Wolfe Islander ferry was in dry dock, Wolfe Island has reversed the population slide over the past 10 years and a number of tourism-related businesses are thriving.

More Stories

- Burn Ban Off in North Frontenac, Addington Highlands - Reduced to Level One in South and Central Frontenac

- The Resurgent Sharbot Lake County Inn and Crossing Pub

- Towards Then End of Trail

- Silver Lake Pow Wow

- Central Frontenac Declares Former Office, Harvey Building, Surplus Properties

- Neighbours Could Lose The War Over Gravel Point - But Still Win The After Battle

- Sydenham Legion Bass Tournament

- From Performing Arts To The Written Word

- Legion Corner

- The Sun Shines On The Parham Fair