Craig Bakay | Nov 08, 2017

In October of 1962, a U.S. U-2 flight photographed a construction site at San Cristobal in western Cuba. The CIA’s Photographic Interpretation Center identified Soviet made SS-4 intermediate range missiles on the site, the kind of missiles the U.S.S.R. used to deliver nuclear warheads.

On Oct. 22, at 7 p.m. EDT, U.S. President John F. Kennedy went on nationwide television announcing the discovery of the missiles, as well as “quarantine” of all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba.

Since the quarantine was to take place in international waters, Kennedy needed the approval of the Organization of American States and before the speech, Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker was briefed by a U.S. delegation. According to Wikipedia, Diefenbaker was “supportive of the U.S. position.”

While no Canadian ship took part in the quarantine, Canadian and U.S. navies had participated in many joint operations in the years prior to the Cuban Missile Crisis and although it ended peacefully through an agreement between Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita Krushchev, Canada’s navy was ready to step in on a moment’s notice if called.

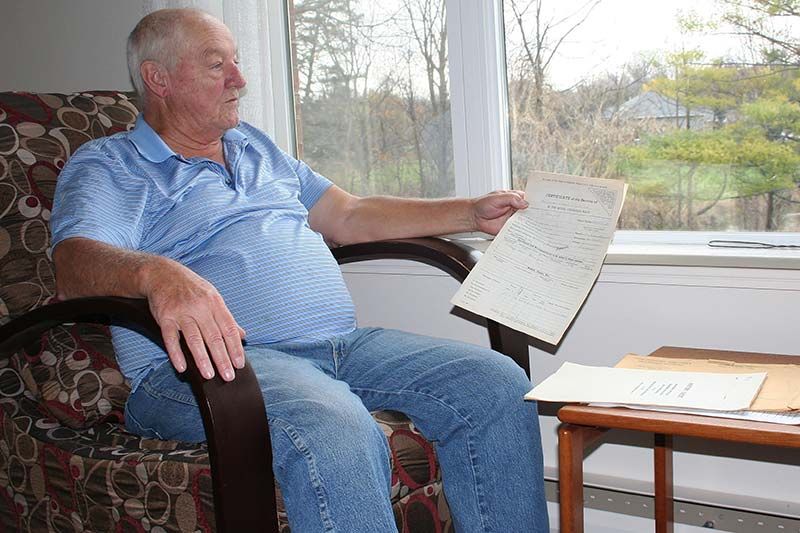

Sydenham’s Bob Stinson knows. He was there.

In May of 1959, Stinson joined the Royal Canadian Navy. He was 17. Because of his young age, his parents Vera and Ken had to sign their permission.

“There wasn’t much going on in Sydenham in those days,” he said. “When I left, my mother made me some sandwiches, wrapped in maps.”

The train trip to Halifax was all naval recruits, heading for the 15 weeks of basic training.

“I had to stay on a little longer,” he said with a sly grin. “I didn’t always do what I was told.”

His first stint was on the frigate HMCS La Hulloise, where he was in the boiler room.

A promotion to EM1 “brought me to the engine room,” he said. “It was a better job.

“You’ve seen in movies where someone in the bridge gives orders into a pipe.

“I was the guy on the bottom end of that pipe.”

Stinson next served on the Destroyer HMCS Athabaskan doing North Atlantic Patrol.

“It was rough on the North Atlantic,” he said. “There was thick ice on all the railings and sometimes you’d look out the portholes and see your sister ship on a wave way above you. The next minute it would be way below you.

“We didn’t even leave the engine room. A guy with a rope tied around him would bring you your meals.”

During that time, he said, they did a lot of joint operations with U.S. ships.

“We went down the east coast of the U.S. stopping at ports in Norfolk all the way to the Gulf Coast of Florida,” he said. “That’s where I had shrimp for the first time.”

In October of 1962, Stinson was on the HMCS Haida, another Tribal Class destroyer.

While the guys in the boiler room weren’t told much, “we knew something was going on,” he said. “We were told to wear our life jackets (the self-inflating kind) and we were issued gas masks.

“There were blackout curtains and I recall everybody on leave was called back.

“We had a full compliment (256) and that sticks in my mind.”

He said the boilers were stoked constantly during that period.

“We were fully ready,” he said. “All we had to do was untie and go.”

Stinson said they mostly played cards (“I got pretty good at bridge”) and pretty much went about their business waiting for a call that never came.

“I don’t remember any talk about what was going on,” he said. “I didn’t think it was that serious.

“I didn’t think much about it — still don’t.”

What he remembers more is the Haida’s last trip, when it was decommissioned and sent to Ontario Place.

“That was one of the best trips,” he said. “In Quebec City, it was during the FLQ crisis and there were armed guards on the ship.”

And he remembers being in Kingston.

“The harbour in Kingston wasn’t big enough for us so we anchored offshore,” he said. “We had a small boat that we ferried visitors in and on one such trip, we recovered a ‘floater’ (deceased body) in the Kingston harbour.”

More Stories

- Kaladar Station - Sometimes the timing is just right

- 50th Anniversary Party for Rural Frontenac Community Services

- Bioblitz Coming This Week at Piccadilly Property

- Committee recommends looking at an accommodation tax in Frontenac County

- Bobs and Crow Lake Shoreline Restoration

- Ellen Fraser is recognized as the winner of the 2025 MERA Award of Excellence in Fine Art and Fine Craft.

- Addington Highlands Treads Lightly Into F Carney Flag Debate Territory

- Simonett Purchase Raises Questions

- Why This Green Could Not Vote Red

- The Sand Is Still Coloured