Jeff Green | Sep 24, 2015

Rightly so, Frontenac Park is considered the hidden jewel of Frontenac County. It is located in the midst of an array of communities and cottage lakes within a stone's throw of Sydenham and is a short drive from Kingston; and yet it is a backwoods park in a unique geological and climactic location. It features the best canoeing, camping and hiking this side of Bon Echo Park, which is also a jewel but one that is less hidden and is also shared between Frontenac and Lennox and Addington.

In his definitive book on the back story about the land where Frontenac Park is located, “Their Enduring Spirit: the History of Frontenac Park 1783-1990”, Christian Barber extensively researched all of the development that took place in and around the park before the idea of a park was floated and eventually acted upon in the 1960s.

Their Enduring Spirit is not only a valuable resource in terms of how the park was developed; it is also an account of the difficulties posed by the Frontenac Spur of the Canadian Shield on those who were unlucky enough to attempt homesteading in its rocky terrain.

The park is located in what were then Loughborough and Bedford Townships, now both part of the Municipality of South Frontenac. Many of the settlers who attempted to make a life in that region did so in the mid-to-late 1800s. There were some Loyalists among them, but there were also a number of Irish immigrants who made their way first to St. Patrick's Church in Railton, and then headed into the wilderness north of Sydenham in search of a new life.

What greeted them was brutal and difficult.

The history of a number of homesteading families forms the core of Their Enduring Spirit. Based on historic records, interviews with descendants who lived on or visited those who lived on the farms, and by walking the land and examining the remnants that are being reclaimed as wilderness lands, a picture of life in the back townships during the first 100 years of Frontenac County emerges.

(An account of the life and times of the Kemp family can be found at Frontenacnews.ca under the “50 Stories/150 Years” tab)

The level of poverty among late 19th Century settlers is reflected in some of the minutes of meetings of both Hinchinbrooke and Loughbrough Townships. In the minutes there are accounts of grants for as little as $1 for families in need after the death of a partner or a debilitating illness.

Families who had settled on the worst pieces of land, who suffered from any kind of ill health, or for some reason were not able to keep up with the demands of clearing land, building shelter, keeping warm in winter and raising enough food, ended up in desperate straits. That is why settlers would take over abandoned fields and houses and only settle the ownership later on, if they decided to stay. Far from disputing this practice, as long as the property taxes were paid the local townships did not question the ownership of the properties.

Mining was one of the few means of getting money for labour, and was also a major impetus for the establishment of the K&P Railroad.

The village of Godfrey, to the west of Frontenac Park, was originally called Deniston after the name of the post office but it was known as Iron Ore Junction by the local population. The Glendower company mined 12,000 tons of iron ore between 1873 and 1880, and later the Zanesville company took over and a spur line was constructed between the mine and the Bedford Station (renamed Godfrey in 1901) of the K&P.

A large deposit of Feldspar was found between Desert and Thirteen Island Lakes, and it was mined, on and off, between 1901 and 1951, producing a total of 230,000 tons in that time.

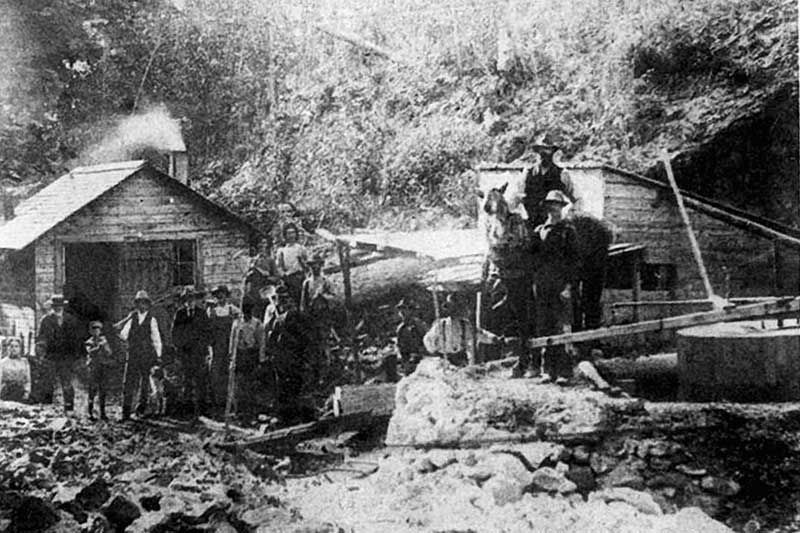

In and right around the park, it was mica that was the most commonly mined mineral, in small mines as a kind of cottage industry and on an industrial scale as well.

There is an account of how a mica mine operated in one of the issues of “The Frontenac News” (not this newspaper but the newsletter of the Friends of Frontenac Park)

Below is an excerpt:

1905 - early in the morning Tom Gorsline, the foreman at the Tett mine, is checking the steam piping as a worker starts a wood fire in the boiler that will provide the steam that runs the drill and the water pumps. The miners had been following a vein of amber mica (phlogopite) since 1899 - the main pit now plunged close to 80 feet into the rocks and water sometimes was a problem. Fortunately, the price for mica is on the rise again and the main vein is still good.

The hand drillers are already at work. Their job is to make holes in the rock to receive the explosives. The drillers are working in teams of two using a method called "double-jacking". One person, the holder, manually holds a steel drill against the rock. The other, the striker, swings an eight-pound sledgehammer hitting the end of the drill. In between the blow, the holder twists the drill to loosen the rock chips so it does not get stuck in the rock. Then the next blow comes with a sharp clank when steel meets steel. They are drilling at a rate of 1.5 to 2 feet per hour. After a half-hour, the holder and striker exchange places so the striker can have a rest. As you can imagine, accuracy is crucial. If the striker misses, the holder could be maimed for life. This is dangerous enough when they are drilling on the floor of the mine, but often the veins are at the roof of a drift or on the wall of the pit.

As soon as the steam from the boiler reaches the right pressure, a miner starts the steam drill. It is faster and easier than hand drilling but the steam drill is enormous, unreliable and unwieldy because of connections with the steam pipes that come down from the surface. As a result, the steam driller is assigned fairly open spaces while the hand drillers work in tight quarters. Drilling is hard and dangerous - there are no hard hats, goggles, or electrical lights - but the dollar a day they are earning helps to feed their families.

Now that the holes are in place, Tom calls the blasters. They make sure the holes are dry, otherwise the charges may not go off. They put the black powder in waterproof covers, attach a proper length fuse, and place it down in the hole. They pack the rest of the hole with clay. The length of the fuse is important or they could meet their maker faster than expected. After a few minutes, all charges are ready. The head blaster gives a signal to Tom Gorsline who orders all miners and equipment out of from the mine. When all is clear, the blaster lights up the fuse and moves quickly out of the way. The explosion rumbles and the ground shakes.

After the smoke and dust settle, Tom sends in the muckers. They have a hazardous job. Everyone knew of George Amey, a mucker at the Birch Lake mine, who lost an eye when his pick hit a charge that did not fully explode. Some muckers sort the ore from the waste while others, with picks and shovels, load the waste rock in a large bucket until it is full. Then one of them yells: "BUCKET." Upon hearing the signal, a man at the surface gets the horse moving on a circular track so that the winch can hoist the bucket up to the top. The bucket is dumped on the tailings pile. As soon as the muckers are finished clearing the debris from the last blast, the drillers begin to make new holes.

Cleaning the mica is the job of cobblers who work on the surface. Some cobblers "thumb trim" the mica by the pit while others are working at the cleaning shop attached to the main mine building, "knife trimming" the mica to remove all traces of unwanted material. They store the clean mica in barrels.

The mica is shipped down the Hardwood Bay Road to Perth Road then north to Bedford Mills. There, the mica will be shipped to a buyer in Ottawa via the Rideau Canal.

The Tett mine operated from 1899 till 1924. It produced 99 tons of mica for a value of $27,279.00. For a few months, it was the largest mica producer in Ontario.

By the 1940s the mica mining boom had passed and most of the homesteads in the area had been abandoned or were on their last legs. It was then that the idea of establishing a wilderness park on the lands in Loughborough and Bedford township that had resisted settlement, and whose lakes (Devil, Big Clear, Otter, and Buck) were not already cut up into cottage lots, was first floated.

In 1954 a Parks Division was created within the Department of Lands and Forests of Ontario (the precursor to the Ministry of Natural Resources.

In 1957, the Kingston Rod and Gun Club submitted a proposal for a new park to serve the growing numbers of people in Kingston and southern Frontenac County wanting to experience the great outdoors, hiking, camping, fishing and the enjoyment of a sandy beach.

The proposal included twenty-seven 200 acre lots in Bedford and twenty-five 200 acre lots in Lougborough, a total of 16.2 square miles, with an option to increase it to 23.7 square miles if the area below Otter Lake was added.

That effort was not successful, and seemed to be dead when Murphy's Point Park on Big Rideau Lake near Perth was established instead.

Five years later, in 1962, another group, the Kingston Nature Club, put forward a similar proposal. This time, even though the cost of purchasing private land for the park had ballooned to $200,000, the proposal was successful. It eventually cost over $1 million to create Frontenac Park, which opened in the late 1960s.

The park's first superintendent, Bruce Page, was the great grandson of Jeremiah, one of the first settlers on the land in the vicinity of what became Frontenac Park.

Among the features of the park, and on the nearby Gould Lake Conservation Area, are hiking trails that pass by and over mica mine sites. In the Park, the 10 km Tettsmine Loop passes by remnants of a log slide from the lumbering days, abandoned mica mines and the remains of McNally Homestead.

At Gould Lake, the Mica Loop passes over several small mine sites and mica minerals can still be seen sparkling in the rock faces.

More Stories

- The Sun Shines On The Parham Fair

- Creating Your Own Weather, Forever and Ever

- Silver Lake Pow Wow Set For A Big Year

- South Frontenac Receives Substantial Provincial Grant for their Verona Housing Project

- South Frontenac Council Report - August 12

- Dumping To Be Curtailed At Loughborough Waste Site

- Central Frontenac Inching Towards Increasing Severance Opportunities

- Addington Highlands Council Report - August 12

- Addington Highlands Council Report - August 5

- Addington Highlands Council Report - August 12