Shabot Obaadjiwan opens culture centre

The Council of the Shabot Obaadjiwan First Nation (SOFN), along with a crowd of members of all ages, gathered last Saturday, May 27 for their annual spring fish fry. But this time, instead of renting or borrowing someone else's hall for the event, they held it in their own new cultural centre.

The SOFN have been working on the centre for a number of years and it is now ready for use. It is located on 50 acres between Highway 7 and White Lake that have been occupied by SOFN under a land use permit from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Fisheries since 2007. The wooded property is included as one of the parcels of land to be transferred to the Algonquins of Ontario as part of the Algonquin Land Claim. It is adjacent to the 500 acres that are reserved for the White Lake Fish Hatchery, and one of the clauses in the Agreement in Principle to the land claim provides for that land to be offered to the AOO if the province ever decided to cease the fish hatchery operation.

“When we went to the MNR to talk about the land for our cultural centre about 10 years ago it was because we did not want to put our own community development on hold while waiting for the claim to be completed. We wanted to build a home base for ourselves, and that is what this building and this land is all about,” said Shabot Obaadjiwan Chief Doreen Davis at the opening of the centre.

The Algonquin Land Claim process seemed set to enter a new phase as the majority of the communities involved, including the Shabot Obaadjiwan, ratified the agreement in principle for the claim earlier this year. However, the majority of voters in a referendum that was held at the only reserve in the claim territory, Pikwàkanagàn First Nation at Golden Lake, voted against the agreement.

“We have all agreed to put a hold on the next phase of the process until the Council of Pikwàkanagàn is able to provide the kind of comfort necessary for those in Pikwàkanagàn who are not ready to sign on,” said Davis.

She said that work continues on many of the details of the complex agreement in the many working groups, with the benefit of participation from members of the Pikwàkanagàn Council, but the entire land claim negotiating team is not meeting to ratify any of the working group decisions until Pikwàkanagàn is ready.

“The land claim always had and will always have bumps and delays along the way, but we are working on our own community all the time,” said Davis.

The Shabot Obaadjiwan raise money through sales at smoke shops that they run in Sharbot Lake and Parham.

“We put everything we raise back into the community, and since our members are integrated into the broader community in the area, we are involved as well,” she said.

Shabot Obaadjiwan donates $1,000 each year to the snowsuit fund at Northern Frontenac Community Services (NFCS). This year, they have been working with NFCS on a snowshoe initiative and are looking forward to working on trail development on private land and some of the land earmarked for park use in the land claim. They also support minor baseball.

“We are working hard developing our cultural centre as well,” said Davis.

In addition to a new pre-fab building, insulation has been installed as well as a wood floor. A front porch has been constructed, as well as a privy.

The next stages are putting in a septic system and plumbing for the centre.

A hand-made birch bark canoe that Shabot Obaadjiwan members built a few years ago is going to be installed inside the front door of the center sometime soon, and other decorations are planned.

“This will be a location where we can live our ceremonial life, our funerals, our weddings, our celebrations,” said Davis, “but we are not trying to exclude anyone either. We will make it available for community use as well.”

The site itself is also under development, as it is transformed from deep bush to a location that can host community ceremonies. Perhaps in time it will host an Algonquin nation gathering, similar to one that was hosted at the Sharbot Lake beach three years ago.

“It takes time, and it takes funds and volunteer labour to do all these things, and we can only do things as we can afford them,” she said.

Algonquin Land Claim Hits Snag

If the Algonquin Land Claim were a train, you might say it went a bit off the rails last week, just it was rounding the corner towards its destination after a long, arduous journey.

The snag that caused the Council of the Pikwàkanagàn First Nation to “take a step back” from the process, in the words of a press release last Thursday (March 17) were the results of a referendum that was conducted earlier this month.

When asked if they supported the Agreement in Principle for the Algonquin Land Claim, which was negotiated by their Chief and council, and the representatives from nine off-reserve communities, 246 members voted in favour and 317 voted against the agreement, 56% against to 44% in favour.

Pikwàkanagàn Chief Kirby Whiteduck said, “Our members ... are currently divided on the proposed AIP and some do not have the level of comfort to move forward at this moment. As a result, our council requires further discussions and consultations with Canada and Ontario to clarify certain issues, to address the concerns of our members and to bridge the divisions in our community.”

For their part, the Algonquin Nation Representatives and the land claim's Principal Negotiator Robert Potts are prepared to give Pikwàkanagàn Council the time it needs to bridge those divisions.

“We are all supportive of the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn as they take the necessary steps to pursue discussions with Canada and Ontario ...” said Clifford Bastien Jr. ,the Algonquin Nation Representative for the Mattawa/North Bay community.

Among the communities in the Mississippi and Madawaska watersheds, the Shabot Obaadjiwan (Sharbot Lake) recorded a 114-5 vote in favour and the Snimikobe (formerly Ardoch Algonquins) recorded a 98-0 vote in favour. The total among the nine off-reserve communities was 3182 in favour and 141 against.

The issue that came up at Pikwàkanagàn in the run-up to the vote was concern over the implications of the AIP as regards self-government, which was a surprise, according to Robert Potts.

“We held extensive meetings throughout the territory and at Pikwàkanagàn after the draft of the AIP was released, and at that time the self-government issue was not raised. It was only in the few weeks preceding the vote that the concern, which was based primarily on misinformation, came up and had an impact on the vote,” he said.

Although he could not completely hide his disappointment about the results of the ratification process, Potts said that the vote was always intended as a non-binding process aimed at identifying issues that need to be addressed, and in that sense it was successful in revealing that the “comfort level among some at Pikwàkanagàn is not where it needs to be. Chief Whiteduck and his council can now address that.”

The other issue that Potts identified as being of concern in Pikwàkanagàn is beneficiary criteria.

“That is something that will have to be finalised before we get to the treaty stage,” said Potts.

While the concept of direct descent from an Algonquin relative, in addition to a connection to an identified Algonquin community, has been used to determine the voters list that was used in the ratification vote, who the ultimate beneficiaries of the claim will be has not been determined.

He said that when a final vote on a land claim treaty is taken, the voting and beneficiary criteria will be identical.

“It will be the beneficiaries who will vote,” he said.

As far as sorting out the issue of self-government at Pikwàkanagàn, Chief Whiteduck indicated last week in an article published in the Eganville Leader, that whether it is tied to the land claim or not, self-government is a priority for his council.

According to research done by Pikwàkanagàn staff, as members inter-marry with non-Algonquins, Pikwàkanagàn will cease to exist within 60 - 70 years because none of its members will have Aboriginal status.

“It would be helpful to further explore self-government and see if we can negotiate and get support for our own constitution under a self-government agreement and determine our own citizenship criteria,” Whiteduck told the Leader.

In an article published in the Frontenac News on March 3, 2016, Greg Sarazin, a former Land Claim negotiator for Pikwàkanagàn now representing a group that opposes the AIP, said that his group is afraid, based on language in the AIP and the statements of federal negotiators, that self government will lead to Pikwàkanagàn losing some of the tax advantages it has under the Indian Act.

“My reading of the AIP, as well as a number of the statements made by negotiators, leads me to be concerned that a commitment to enter self-government negotiations has already been given by Chief and Council and that the terms committed to will extinguish Pikwàkanagàn members' rights and bring an end to Pikwàkanagàn,” he said.

With one side claiming that self-government is the only way for their community to survive, and the other claiming it is a death sentence for their community, it could take some time before a land claim process that is associated with self government to get back on track.

Pikwàkanagàn Protest Against Land Claim AIP

by Jeff Green

A movement has been growing among many of the members of the Pikwàkanagàn Algonquin First Nation, and on Sunday (February 28) it bubbled over in a peaceful march by demonstrators in front of the council office on the reserve.

Led by the Grandmothers of Pikwàkanagàn, the protesters are calling for the elected council of Pikwàkanagàn, which is the only Algonquin reserve in Ontario, to reject the Agreement in Principle (AIP) for the Ontario Algonquin Land Claim.

A vote on the AIP is scheduled for Saturday, March 5 in Pikwàkanagàn, and the protesters have given their council until March 4 to respond to their demands.

The protest follows a community meeting that took place two weeks ago, and a subsequent petition, demanding that the chief and council withdraw Pikwàkanagàn from the ratification vote and begin discussions with the community on the terms of an acceptable AIP.

Pikwàkanagàn council members have a lot at stake in seeking ratification of the AIP, as all of them are part of the team that negotiated it, along with representatives from nine non-status Ontario Algonquin communities.

A report from Postmedia says that Pikwàkanagàn Chief Kirby Whiteduck addressed the demonstrators on Sunday, and said that the AIP is not a legally binding document but only sets the stage for further negotiations.

Greg Sarazin was chief of council and one of the negotiators for Pikwàkanagàn during the first 10 years of the process. He is now the media spokesperson for those in the community who oppose the AIP and on February 22, he delivered a press release outlining community concerns.

"Details of the proposed AIP have just recently come to light and members of the First Nation are coming to realize the scope of the damage that will be done to them, their children and to Pikwàkanagàn 's future.

“Over the past several years, community members have provided input to the chief and council on what was acceptable and what would not be acceptable in a settlement of the Algonquin land claim. Our concerns have fallen on deaf ears. The proposed AIP contains language that leads to a loss of identity as an Algonquin First Nation.”

As Sarazin explained in a telephone interview early this week, there are a number of clauses in the AIP that raise concerns about its impact on the future of Pikwàkanagàn. He said that when he raises those concerns with the council and Chief Kirby Whiteduck, “There is no clarity; there are just statements and vague promises that clearly contradict what is written in the AIP document. The AIP itself is a written document that is being voted on.”

The AIP says that with the agreement, Algonquin rights will be “extinguished”. This is something that will affect the Pikwakanagan members in particular, since among the 7,000 Algonquin electors qualified to vote on the AIP, they are the only ones who have status under the Indian Act.

In particular, Sarazin points to provision 12.4.1 of the AIP, which says that “Section 87 of the Indian Act will have no application to any Beneficiary, Algonquin institution or Settlement Lands as of the Effective Date."

Section 87 is the provision in the Indian Act that exempts status Indians living on reserves from the tax system.

“My reading of the AIP, as well as a number of the statements made by negotiators, leads me to be concerned that a commitment to enter self government negotiations has already been given by Chief and Council and that the terms committed to will extinguish Pikwàkanagàn members' rights and bring an end to Pikwàkanagàn.”

Sarazin said he is afraid that Pikwàkanagàn will be turned into a municipality like all others in Ontario, and “municipality designation means extinguishment of constitutionally protected section 35 Aboriginal rights and assimilation of Pikwàkanagàn. There is no indication that there is any plan for community members who will suddenly have to pay taxes on what is no longer Indian reserve lands.”

There have also been statements by the federal government that only heighten Sarazin's fears.

In 2012, in a letter to municipal chief administrators, federal land claim negotiator, Brian Crane, explained the federal government's position on the future of Pikwakanagan after the land claim is finalized.

“12.4.1 reminds the Algonquins that the s.87 Indian Act tax exemption will be discussed in the context of these self-government negotiations. The federal government has made its position clear that according to Canada's policy, after a self-government agreement has been negotiated for Pikwàkanagàn, the Pikwàkanagàn reserve will cease to exist and the s.87 tax exemption will not apply.”

In addition to being a spokesperson for the community group, Greg Sarazin owns one of the dozen smoke shops on the reserve who together employ around 60 community members.

“If Pikwàkanagàn ceases to be a reserve all the smoke shops will be out of business. The entire economy of Pikwàkanagàn will be wiped out,” he said.

According to Sarazin, the community meeting, the petition, which he said has been signed by over 60% of the community, and the grandmothers' protest, all amount to a community decision-making process.

“If council is looking for direction from the community, they already have it,” he said.

There may be a protest on Friday as the Grandmothers of Pikwàkanagàn will be seeking answers from council in advance of Saturday's scheduled vote.

Land claim elector criteria coming under scrutiny as vote nears

Seven thousand and seven hundred Algonquin electors are eligible for a ratification vote on the Algonquin Land Claim Agreement in Principle between February 29 and March 7. Voting will take place in nine off-reserve communities, including Sharbot Lake, as well as at Pikwàkanagàn First Nation.

The claim has been 25 years in the making, and now that the vote is near, questions that have been put aside for at least the last 10 years are now being raised.

A report commissioned by the Kebaowek First Nation, an Algonquin community in Quebec also known as Eagle Village, which has a substantial territorial overlap with the Ontario claim, has researched the origin of a sample group of 200 Algonquins of Ontario electors. The results surprised the researchers; 72 of the 200 electors they looked at had only one Algonquin ancestor, stretching from four to six generations back.

“If these examples are typical of the AOO list, then it represents a triumph of genealogy over common sense…Call it the homeopathic approach to Aboriginal Title and Rights - a little drop will do you,” concluded the report, according to an account by APTN (Aboriginal Peoples Television Network)

The report goes on to say that “None of these people would qualify as electors for any existing comprehensive agreements or modern-day treaties.”

The Kebaowek First Nation has a reason to be skeptical about the Ontario Algonquin Land Claim. Although they are based in Quebec, they lay claim to about 300,000 hectares on the Ontario side of the Ottawa - land that is included in the Ontario claim.

The revelations about the lineage of Algonquin electors is not a surprise to anyone who has been following the claim over the last dozen years or so. The decision was made to include as an elector any individual who could prove they are a “direct descendant” from an Algonquin individual and could also demonstrate a cultural connection to an Algonquin community.

At a meeting at the Catholic church hall in Sharbot Lake in 2003 or 2004, representatives from the nine non-status communities as well as the entire Pikwàkanagàn Council debated the question of “blood quantum” for beneficiaries of the claim.

At that meeting, the lawyer Robert Potts, who had taken on the role of chief negotiator to the claim just a few months previously, sought common ground between the position taken by the Pikwàkanagàn Council that a minimum “blood quantum” was needed for legitimacy, and the position of the non-status communities, who argued that direct descent, no matter how far back, was sufficient.

The compromise that Potts came up with was to say that direct descendants, as long as they can be vouched for by a community that was already known to the process at that point, was sufficient to gain someone the right to be an elector, giving them the right to vote in the election of their representative to the land claim negotiating table, and the right to vote on an agreement, should one ever be negotiated.

The entire seven-member Pikwàkanagàn Council would sit at the negotiation table, as well as one representative from each of the nine non-status Algonquin Communities.

The further question of beneficiary status was left to future negotiations. Members of the Pikwàkanagàn Council did not make a commitment at that meeting but since the negotiations have proceeded on that basis, it is clear they decided to stay with the process under those terms.

To my knowledge the beneficiary status has never been finalized, but since all the proceeds of the land claim will be going to an Algonquin corporation based in Pembroke and no individuals from those communities will receive a payment of any kind, beneficiary status may not be as important as people envisioned back in 2003.

Potts defended the way electors are verified to APTN this week, saying, “Why is that a problem if people have been practicing their culture over five generations? The Indians that are part of this country are not all status…You don’t ignore non-status people….It is hard for some of the old hard-line status-type people, who feel it is an incursion of their rights.”

As I have written before, there are problems with both sides of this debate. The idea of “blood quantum” leads only to fewer and fewer people having the right to call themselves Algonquin. As an elder from the Alderville First Nation said to me years ago, “We like to think of ourselves as a nation, but what nation tries to limit its membership? Nations need to grow and get stronger, not shrink and get weaker.”

On the other hand, a direct descendant can have nothing more than a forgotten great great grandmother who was listed on a census as of Algonquin heritage in part. The provision for a “cultural connection” is, in practice, a fuzzy requirement. How do you quantify that? When Mr. Potts says people have been “practicing their culture”, what does he mean when the entire culture was underground until very recently? Pride in Indigenous heritage is a pretty recent phenomena in Canada.

Now that this question of blood quantum versus direct descent, which has been lurking for a dozen years, has come to the fore, there are other questions about the Algonquin electors and the nine communities that might be raised as well. A number of communities, including the Ottawa, Bancroft and Ardoch communities, have dissident former members who claim they have been pushed out of leadership roles in those communities by the land claim hierarchy itself, for no other reason than their opposition to the bargaining position that has been taken at the land claim table as the agreement in principle was being negotiated.

We will look at one of these internal issues in next week's paper.

Opposition re-surfaces as land claim vote nears

A ratification vote is set for late February and early March concerning the Agreement in Principle (AIP) for the Algonquin Land Claim in the Ottawa Valley.

The Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation (APFN), the only community in the territory made up of “status” Algonquins under the Indian Act of Canada, joined with the Algonquins of Ontario (AOO), which is made up of nine off-reserve “non-status” communities. Together they negotiate the AIP with the governments of Ontario and Canada.

The AIP was presented to the public in early 2014. Both of the governments have now ratified it, leaving the ratification vote among Algonquins as the final hurdle. If ratified by the Algonquins, final negotiations towards a formal land claim treaty will begin. Those negotiations are expected to take five years to complete, which would make the land claim process, which began in 1992, a 30-year odyssey.

Over the last 25 years, a number of people have walked away from the land claim process for a number of reasons, and as the vote nears next month they are starting to come forward with concerns over the legitimacy of the vote, and the process that preceded it.

Jo-Anne Green put out an open letter this week. She writes on behalf of herself and her mother, Elder Eleanor Baptiste Yateman, the great grand-daughter of Chief John Baptiste Keeigu Manitou from Baptiste Lake, northwest of Bancroft, where Eleanor was born and raised.

Green says that her mother, who now lives in Peterborough, was in the closed meetings before the land claim began. “When she found out the way the claim was proceeding and that the non-status were going to be used for head count only, she decided to resign, but that is not to say she had resigned from working on attaining the rights for our indigenous people; it is quite the opposite.”

The letter goes on to say that APFN not only marginalized the non-status population, they created false communities and also downplayed the Nippissing lineage of local people.

One of the nine communities that make up the AOO is the Bancroft/Baptiste community. According to Jo-Anne Green and Eleanor Yateman, “The Bancroft/Baptiste community is not legal. We can say this because we know our lineage and our history ... the Nipissing history is a big part of the rights and title to the land claim.”

Green says that she, along with her mother, “have been exposed to ridicule, silence tactics and intimidation; all this by an institution that purports to represent Algonquin people”. She says there are others who share their concerns.

She also says that, “A great number of pertinent documents support our allegations”; that the “land claim needs to be exposed for what it is”; and that the “claim has many layers of deception.”

Film about Barriere Lake Algonquin Reserve to be shown in Sharbot Lake

Martha Steigman, a documentary film-maker from Halifax, will be presenting her film, Honour Your Word, at the United Church Hall in Sharbot Lake at 2 pm this Sunday (November 9). The title Honour Your Word is taken from a slogan that is used by residents at Barriere Lake, an Algonquin reserve that is one of the poorest in Canada. It asks the Province of Quebec and the Government of Canada to honour a conservation and resource-sharing agreement that was negotiated with them that was negotiated in 1991.

The film follows the lives of two young leaders: Marylynn Poucachice, a mother of five, and Norman Matchewan, the soft-spoken son and grandson of traditional chiefs. Both spent their childhoods on the logging blockades their parents set up to win a sustainable development plan protecting their land. Twenty years later, Norman and Marylynn took up the struggle of their youth, to force Canada and Quebec to honour their word.

The context for the barricades at Barriere Lake is familiar. The community was in disarray over leadership, and the Province of Quebec decided to move in and impose third party administration, angering both sides in the dispute.

Underlying the internal tension and anger over the imposition of governance, is the ever-present disconnect between the Algonquin community's connection to the vast tracts of land surrounding their tiny 59 acre reserve, and the arrangements that had been made between government and logging interests.

Director Martha Steigman spent four years shooting this documentary, which challenges stereotypes of “angry Indians.” Honour Your Word juxtaposes starkly contrasting landscapes - the majesty of the bush, a dramatic highway stand-off against a riot squad, and daily life within the confines of the reserve - to reveal the spirit of a people for whom blockading has become an unfortunate part of their way of life, a life rooted in the piece of Boreal Forest they are defending.

The film was released this past March, in the midst of many changes at Barriere Lake. There has been a recent Supreme Court ruling supporting the position of the current Band Council in its quest for land and resource rights outside of the context of the comprehensive land claims policy. A policy the federal government has been pursuing for 20 years that requires First Nations' Aboriginal rights to be extinguished with the signing of land claims agreements.

After the one-hour documentary is shown, Martha Steigman, Marylynn Poucaciche and up to three other Barriere Lake community members will be on hand to answer questions and share coffee and food with the audience.

The film is being presented by the Ardoch Algonquin First Nation in support of their sister community. Admission is free, and there will be an opportunity to donate to the community of Barriere Lake.

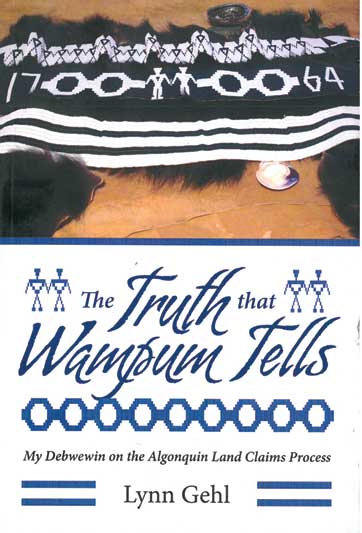

The Truth that Wampum Tells

The Truth that Wampum Tells: My Debwewin on the

Algonquin Land Claims process, by Lynn Gehl.

Ever since the draft Agreement in Principle to the Algonquin Land Claim was released in late 2012, there have been political debates and controversies among non-Algonquin political groups, ranging from township councils, to the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters, the Federation of Ontario Cottage Associations and others.

The issues that have been raised range from the specific lands that are included in the claim, the nature of the transfers, and more. At some of the public meetings things were said that revealed a level of mistrust and resentment, an uncomfortable level in many cases.

Later in 2013 it came out publicly that a large number of people in the Sharbot Lake area, members of the Shabot Obaadjiwan First Nation, some of them in leadership roles, had been removed as Algonquin electors by virtue of an appeal process that determined their Algonquin descendency is unproven. The fallout from this devastating process has been dealt with internally by the Shabot Obaadjiwan and local families

Meanwhile a ratification vote on the Agreement-in-Principle is still pending.

Into this context comes a book by Dr. Lynn Gehl, based on her doctoral thesis, which not only looks at Algonquin history but also details the first 15 years of the Algonquin Land Claim process, a process she walked away from in 2005. As readers of the Frontenac News will know, Dr. Gehl is not the only Algonquin person to walk away from the Land Claim process in recent years.

Dr. Gehl's book is the second fully researched book on the land claim and its underpinnings, following "Fractured Homelands" by Bonita Lawrence.

Gehl calls her book “My Debwewin on the Algonquin Land Claims Process”, and she explains what a Debwewin is in the forward to the book. The concept is complicated, but in the most simple sense it refers to the knowledge of the heart and knowledge of the mind, although it might be more accurate, in the case of this book, to talk about knowledge of the self gained by experience mixed with a rigorous academic examination of source material.

As in the Lawrence book, those Algonquins who oppose the direction that the land claims process has taken are easy enough to find and quote, whereas those who are internal to the process do not speak. For several years there has been agreement among negotiators not to talk about the process except in a very prescribed manner.

The Truth that Wampum tells weaves Gehl's own life story with some historical background about how the Ontario Algonquins developed and how the land claim got its start. As a close descendent of people who were born and raised at Pikwàkanagàn, Gehl has a unique perspective on that community and on how the Indian Act defines native status.

The book is also a step by step account of the twisted path of the land claim from the late 1990s until 2005. It ends just after the initial impact of the current chief negotiator and legal counsel to the claim, Robert Potts, who came on in 2005.

The Truth that Wampum tells is an essential read for those interested in the background to any of the current debates about where the land claim is going, and it also clearly delineates how hunting agreements entered into by the Ministry of Natural Resources and the leaders/chiefs who are negotiating the claim have played a significant role.

Anyone who is interested in the role of 'blood quantum' in the land claim, the very different world views of the Pikwàkanagàn Council and the 'non-status' negotiators who have been sharing a negotiating table for many years now, and the continuing impact of colonialism on Aboriginal communities of all kinds, will find a unique perspective in Dr. Gehl's Debwewin.

For information about The Truth that Wampum Tells, contact Lynn Gehl at Lynngehl@gmail.com

Group_seeks_to_halt_Land_Claims_Process

Feature article February 17, 2005

LAND O' LAKES NewsWeb HomeContact Us

Group seeks to halt Algonquin Land Claims Process before it starts up again by Jeff Green

A group calling itself The Algonquin National Advisory Committee (TANAC) has provided notice of their intention to proceed with a class action suit against everyone involved in the Algonquin Land Claims process.

Michael Swinwood, a lawyer from Almonte, has served notice of the

pending suit to the Province of Ontario, the Government of Canada, the

Council of the Pikwakanagan Reserve (Golden Lake), and two entities

which have sprung up to provide representation to non-status Algonquins

in Ontario.

Michael Swinwood, a lawyer from Almonte, has served notice of the

pending suit to the Province of Ontario, the Government of Canada, the

Council of the Pikwakanagan Reserve (Golden Lake), and two entities

which have sprung up to provide representation to non-status Algonquins

in Ontario.

This suit is coming about as Algonquin Land Claims Chief Negotiator Robert Potts is in the midst of calling elections for Algonquin National Representatives, individuals who are to be elected by people of demonstrable Algonquin descent and have chosen to affiliate themselves with one of seven communities within the Ottawa Valley in Ontario.

These off reserve, so-called non-status Algonquin Communities are to sit at the negotiating table along with the Chief and Council of the Pikwakanagan reserve, which is located at Golden Lake. Pikwakanagan is the only reserve within the Land Claim territory.

The Algonquin National Advisory Committee held a meeting last weekend in Sharbot Lake. About 50 people attended, from various parts of the Algonquin territory, with a concentration coming from the Sharbot Lake vicinity. The Algonquin Drum from Pikwakanagan was in attendance, and Michael Swinwood addressed the meeting. He explained the perspective from which the class action suit he is propagating for the Algonquin Nation is coming from.

The Algonquin Nation is sovereign, he said, there has never been a treaty signed ceding Algonquin lands to the Crown. The Land Claims should be conducted on a nation-to-nation basis between the Algonquin Nation and the Government of Canada.

Swinwood argued that the Province of Ontario needs to be at the table only because they have had mineral rights granted to them from the government of Canada, but that Ontario cannot be a principal to the negotiations. He also said that cutting Ontario and Quebec Algonquins off from each other was part of the divide and conquer strategy that has been perpetrated on Aboriginal peoples throughout North America.

There are nine Algonquin Reserves on the Quebec side of the Ottawa River, and there has been no Land Claims Process initiated for Quebec Algonquins.

Michael Swinwood also noted that, according to a Royal Proclamation in 1763, Aboriginal peoples are not to be disturbed and that their territory is not to be taken from them. Further, he stated that Section 25 of the Canadian Constitution Act of 1982 states that the Royal Proclamation of 1763 is a living document in terms of aboriginals.

Bob Lavalley, who comes from the Algonquin Park region, chaired the meeting. He said he didnt want to engage in name calling, but that there are serious problems which make the entire Land Claims Process untenable. For one thing, the way it is set up, the people that have been engaged in the process from the Algonquin side are being paid by the government, from the proceeds of whatever settlement they come up with, to carry on the negotiations. How can you negotiate if you are being paid by the other side? he asked.

Lavalley made reference to two bodies that have been developed among non-reserve Algonquins: the Algonquin National Negotiating Directorate (a not-for- profit corporation) and the political body called the Algonquin National Tribal Council. Under the rubric of these institutions, offices have been set up in communities throughout the region, including two in Sharbot Lake. The election process that Robert Potts has set up is an attempt to move on from some of the internal problems of these two previous bodies and focus directly on the Land Claims Negotiations.

The negotiations, which were initiated in 1991, are officially frozen from the perspective of the Ontario and Canadian governments, pending the development of a negotiating team to represent the Algonquin side. Robert Potts is hoping the Algonquin National Representatives will be in place in time to resume negotiations later this year.

Robert Potts has said that the fact that both the Provincial and Federal Governments are prepared to negotiate makes this an historic opportunity for Algonquins, one that may not come again.

This perspective is countered by some, including Lynn Gehl, who wrote in a recent issue of the Anishnabek News, It is my contention that the Algonquin need not sell their land and need not fear that this is our last chance, as others threaten. What the Algonquin need is to demand the time to repair the present fractured and unorganised Algonquin Nation. It took the coloniser well over 300 years to create this position of weakness and it will take us longer than 10 years to repair the damage.

At their meeting in Sharbot Lake, TANAC formed a committee which is devoted to contacting as many Algonquins as possible, on both sides of the border, to inform them of their perspective, to ask them to withdraw their support from the Land Claims Process and put their names behind Michael Swinwoods class action suit.

Michael Swinwood admits the class action suit aims high. It claims all government land within the Ottawa Valley, which includes the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa, and asks for $13 billion in damages.

Letters_March_17

Letters March 17 2005

LAND O' LAKES NewsWeb HomeContact Us

Re: Coyotes and WolvesI am writing to you about, an article that appeared in your newspaper in December called Wolves or Coyotes. (Nature Reflections column December 9, 2004)

The article in your newspaper referred to a study by Theberge et al that was published in the Canadian Field Naturalist.

I would like to try to help your readers understand the wolf issue properly with science and true biology, and remove all the confusion if that is possible. All of this can be verified on MNRs web site or in your library.

The wolves we have in Ontario today are the Grey Wolf, The eastern wolf and the Coyote.

First The Coyote is found from in every corner of this province and are the most prominent of the wolf family in the southern part of the province.

Yes you do have Eastern wolves and Coyotes in your part of the province. But as far as wolves or Coyotes breeding with dogs goes, it is a very rare thing, as most times the wolves or coyotes consider the dog a threat and kill them. So what you are probably seeing and hearing are coyotes.

Next The issue of the so called Algonquin Wolf: these wolves are all members of the same family, the eastern wolf and there is no such thing as the Red Wolf in Ontario or in Algonquin park.

Dr White of Trent university did an in depth DNA study in March 2001 on all the hides from the trapping houses and found that the Eastern Grey wolf and the wolf that Theberge called the red wolf were exactly the same wolf and there is no distinct wolf to Algonquin park nor do they have a distinct DNA from the other eastern wolves in Ontario.

I was part of a group of stakeholders that Mr. Brent Paterson from MNR gave a presentation to in December, on the wolves of Ontario and Algonquin Park.

The study has showed that in fact there are more wolves in Algonquin Park today than when D. H. Pilmot did his work in the 1960s, and that the park is at its maximum carrying capacity for the amount of prey species available (beaver & deer and moose).

Last year MNR had tracking collars on 146 wolves in the park and have found at least 28 packs ranging in size from as few as three animals to 18. He also noted that there are no areas in the park where wolves were absent, as Mr. Theberge has suggested.

These packs of wolves have home ranges that overlap each other and expand outside the park boundaries as the packs from outside the park overlap inside the park boundaries.

I would also like to point out that the Eastern wolf is not endangered and have been healthy and stable in Ontario for 20 to 30 years, with a population of over 10,000 and is thriving, all the way from Manitoba to the east New Brunswick, according to MNRs own biologists in the field.

The Committee on the status of Endangered Species in Canada ( C.O.S.E.W.I.C ) determined in 2002, that the Eastern Wolves was in no way endangered. The committee also expressed no concern about over harvesting of these wolves.

Basic wolf biology tells us that wolf populations can sustain harvests of 30 or 40% without any negative impact. At the present time the harvest in Ontario is less than 6% each year. Wolf researcher, Mr.Douglas Pilmot, demonstrated this decades ago when Wolf Control was found to be ineffective in the park. The MNR in Algonquin Park were killing 55-60 wolves annually, in the 1950s and it did not reduce the population.

Dr Pilmot indicated that the saturation point for wolves in Ontario was 2.9 wolves per 100 sq Klm and we are at that point right We feel that Mr. Paterson should have been given more time to prepare an accurate assessment on this issue before any restrictions were made permanent around Algonquin Park.

The hunters and trappers of this province are your front line conservationists we spend millions of dollars every year on wildlife and wildlife habitat improvement. If the outdoor community recognizes a legitimate reason for regulations on species-specific hunting, we will be the first to condone the actions needed to regulate and preserve that animal.

Given all the facts, numbers, and data collected to date we find that the Eastern Grey Wolf and the Coyotes are not only abundant but their population is growing rapidly.

If this government is not careful they may make a decision that could only be compared to the spring bear hunt and we know what a disaster that has turned out to be.

Please take the time to investigate Mr. Patersons report at your earliest convenience. You can contact him in the Peterborough office of MNR.

John Bell, Lindsay, Ontario

Re: Same-Sex Marriage

Exerpts from A Companion to Catechism by Arthure W. Lochead, D.D. The United Church Publishing House, 1945. What is sin? Sin is mans refusal to trust God and do His will, and his following the evil desires of his own heart. -page 17: What are the consequences of sin? Sin brings upon men God's displeasure, and condemnation, breaks their fellowship with one another, corrupts their nature, and involves the world in moral confusion and distress.---Page 22: What did Jesus Christ do to overcome sin? Jesus took our sin upon Him and bore it on the Cross, and God set His seal on Christ's work, by raising Him from the dead, and exalting Him as Lord of all. page 23: What must we do to be saved? If we are to be saved, we must repent of our sins, and commit ourselves to Christ in life and death. page 27, What is the task of the church? To minister to the needy, to wage war on evil, and strive for right relations among men----.page 74- What duty do husband and wife owe to one another? It is the duty of husband and wife, as Partners for life, to give one another Love, Fidelity, and Co-operation, married life is a precious gift of God. In married life man and woman double their joys and halve their sorrows. The love that a husband bears to his wife should be a picture of Christs love to the Church and the love of a wife to her husband should be deep and sincere as the love of a believer to Christ. ..The Christian ideal is that there be no breakdown of the marriage tie, Husband and wife are one till death parts them (Mark 10:2-12 Matt:19:3-9

This book has a lot more to say about the holiness of Gods own church, and that is good enough for me.

Donna Carr

Mitchell Creek Bridge

The Federal Government's bureaucratic heavy machinery is about to mow down local solutions to bridge repair over a tiny creek in South Frontenac Township. Collateral damage will include major new township expenses, weeks of traffic headaches for local residents, the destruction of a picturesque waterway, and potentially serious environmental impacts.

It didn't have to be this way.

Mitchell Creek is just a small, pretty stream that runs between Desert Lake and Birch Lake. The wood-and-steel bridge over the creek is an integral part of the lively surrounding community which includes year-round residents, summer cottages, Snug Harbour Resort, and Mitchell Creek Outfitters. The narrowing of the bridge to one lane serves an important traffic-calming function in this neighbourhood, where kids and dogs abound.

Traffic calming occurs in the stream, as well. The bridge is high enough to allow canoes and small motorized craft to pass underneath. It is also low enough to inhibit access to larger boat traffic, particularly in the early spring when the water is high and birds are nesting. This is important in a narrow and ecologically sensitive waterway, where the eggs of loons and other nesting waterfowl can easily be swamped by the wake of large speedboats. All summer, visitors to Frontenac Park use public access at the bridge to launch their canoes, rewarded with a quiet wildlife-enhanced paddle up the creek to their campsites.

A simple repair is all that is needed. Engineers hired by the township last year came up with a cost-effective proposal to replace the steel girders. Their solution would maintain the essential character of the bridge, cause minimal disturbance to the stream and limit traffic disruption for residents on upper Canoe Lake Road to a matter of a few days. Many local residents expressed their strong support for this proposal through their letters and participation in a public information session last summer.

It all seemed quite straightforward until the federal government waded in. Transport Canada's Navigable Waterways Protection Act has rules about bridges rules, it seems, that apply blindly to all bridges, whether the passageway goes over the St. Lawrence River on a major highway or over a tiny creek on a backwoods road. And those rules say that Mitchell Creek's new bridge repairs must ensure a five-foot clearance over the waterway's high water mark.

Five feet! What's five feet?

Five feet means a major development that will excavate roadways on both sides of the creek. It means weeks of long detours to get to work and school and critical access problems for emergency vehicles. Five feet means tens of thousands of dollars (or much more) in additional and unnecessary expenses for the township and its taxpayers. It means a narrow, hazardous waterway overrun by high-powered motorboats speeding between lakes.

Five feet also means a whole host of new problems. Will the new and wider bridge block access to the public boat launch? If so, will there be costly expropriations of land to maintain public boat access? Will larger, faster boats in the narrow creek threaten the safety of canoeists and other non-motorized travellers? If so, will there be a whole new round of investigations regarding speed limits and channel markers?

To the Federal Government, it doesn't seem to matter that the existing bridge over Mitchell Creek is perfectly satisfactory, maintaining the liveable community and rich natural environment that we cherish. To the Feds, rules are Rules.

But it matters to us to the taxpayers, local residents, and users of Mitchell Creek. We care about this community and its safety. We care about maintaining and supporting a local environment abundant with thriving plant and animal species. We care about the squandering of many thousands of dollars on a wasteful and potentially damaging project.

Mitchell Creek is not the Thousand Islands Bridge. Exceptions to rules can and do happen. The Desert Lake causeway, for example, was built long after the Navigable Waters Act came into effect, but it has no high water clearance whatsoever.

Township Council must not allow South Frontenac to be bullied by federal bureaucratic rules that attempt to shoehorn every community into the same ill-fitting shoes. I urge Council to face up to the Feds and demand that room be made in the regulations for a little bridge that needs to survive.

Nancy Bayly Hartington, Ontario

Multiple chemical sensitivities

If I were sitting in a wheelchair, my disability would be obvious and severe. However, my disability is an invisible one that is not well known or understood.

I have multiple chemical sensitivities (MCS) or environmental illness or sensitivities which is afflicting a growing number of people in our society. This diagnosis has been confirmed by a physician, a leading specialist in environmental medicine, and formally acknowledged by the government of Ontario.

Because this illness so drastically affects my ability to function around other people, I feel compelled to educate my community about it. I must hasten to add a thank you to those who continue to accommodate my needs.

MCS is a complex of symptoms that are distressing and confusing, especially to the person suffering from them. The causes are toxic chemicals in the "environment", in the air and water and food and everything around us. A reaction is triggered by exposure at lower levels than those that would affect the "average" person. The treatment is basically one of avoidance, as there is nothing else to be done to avoid a reaction or to treat it when it happens. The reactions vary and I will return to this later. The important point here is that avoiding the toxins is the only treatment.

Now, I am not saying all this off the top of my greying head. The information comes to me from the specialist in environmental medicine and from the common literature on the subject.

If this publication will give me the space, I will discuss in more detail the substances that cause reactions and what the reactions are, the differences between allergies and chemical sensitivities and my own personal experience of this illness later.

In a letter to another woman even more devastated by this condition than I am, Commissioner Norton of the Ontario Human Rights Commission writes explicitly, "It is the Commission's policy position, ., that environmental sensitivity is a disability and is thus protected under the Code.

"The Commission encourages individuals and organizations to be aware of their human rights obligations and to consider the needs of persons with chemical sensitivity including the duty to provide appropriate accommodation short of undue hardship. Failure to do so may contravene the Code."

Next time, I will go into just exactly what all this means for my situation and your role in it. Meanwhile, please think of me when you splash on some cologne or put fabric softener in your laundry because, though you may consider it none of my business, yet when we meet at the community centre, library or grocery store, it affects me in a most detrimental way.

Jennifer Tsun, McDonalds Corners

Re: Same-sex marriage

This is in reply to a letter in the Frontenac News by Rev. Jean Brown re same-sex marriage (March 3, 2005)

I do not agree with the statement: There are many ways of interpreting the Bible. The Bible is the divine revelation of God and you cannot dispense any part of it. Whether it is modern scholarship or 2000 years ago, the Bible cannot be changed to meet the sins of the world.

Genesis 19 gives an account of the sexual sins in Sodom and Gomorrah, and what God did to the cities, verses 24 and 25. You can also read it in Leviticus 18: 22; Romans 1: 24 27; and 2 Peter 2:6. I do not believe that this refers to anything but homosexuality, same-sex marriage and it cannot be an honourable marriage.

God created everything, including male and female, and then He said, multiply and replenish the earth. Can you give me an inkling of how this can be done in same-sex marriage? You can call it whatever you want, but God calls it sin, and He will only let sin go so far, and then He will do the same as He did to Sodom and Gomorrah.

Yes, we will all stand before God and give an account of ourselves, and the way society is going it wont be long.

Grace Tooley

Elections_to rejuvinate_process

Feature articleApril 28, 2005

LAND O' LAKES NewsWeb HomeContact Us

Elections intended to rejuvinate land claim processby Jeff Green

The Algonquin land claim, which has been on hold for years now, might start moving forward again, and Algonquin Chief Negotiator Robert Potts is hoping to set up a preliminary meeting with Canadian and Ontario Officials in May, to set up a full resumption of negotiations this September.

Early this month, four of nine Algonquin communities have acclaimed what are being called Algonquin Negoritation Representatives (ANR) and five others will be holding elections in the next two weeks. An election was held for the Sharbot Lake representative this Monday.

The nine Algonquin Negotiation Representatives will then join with members of the newly elected Council of the Pikwakanagan First Nation of Golden Lake, representing Algonquins of status under the Canadian Indian Act, in forming a negotiating group in order to resume Land Claims negotiations with the Federal and Provincial governments. Negotiations have been on hold for several years now, awaiting negotiators from the Algonquin side.

The process has not been without controversy, however, with critics charging that the timing of all- candidates meetings and mail-in ballots were set up in an unfair manner.

The process was organized and administered out of the Toronto office of Algonquin Chief Negotiator Robert Potts, and critics charge that the time frames and practices established did not allow for enough information to flow to electors, ultimately providing an unfair advantage to candidates who were already well known in their communities.

One such critic is Melinda Turcotte, a candidate for the ANR role in the community of Sharbot Lake.

In Melinda Turcottes case, her opponent Doreen Davis is well known by the Sharbot Lake electors since she is the Chief of the Sharbot Lake Algonquin First Nation under the Algonquin National Tribal Council.

The all-candidates meetings were scheduled two months prior to the date they were to take place, Turcotte told the News, but I was only notified ten days prior to the date they were set for. This to me is unfair. In my case I had a prior commitment on the date of the candidate meeting that could not be changed.

Turcotte sent her husband to the meeting, which took place on April 14 at St. James Church in Sharbot Lake. The election ballots were also sent out before I had a chance to send out my biographical information, and before the candidates meetings, Turcote said. This is a serious problem because the ballots included an encouragement to fill them in and send them back as soon as possible. How was I supposed to get my message out to people who had already voted?

And finally, Turcotte adds, if I decide to appeal the result, the appeal process gives me 24 hours after the results are announced to file an appeal and pay $200 to do so. Why only 24 hours, and why $200?

For her part, Chief Doreen Davis said she found the election had been professionally organized, and she had no problems with the way it was run. I will say that I also had a conflict with the date of the all-candidates meeting, but I rescheduled in order to be available for it.

Doreen Davis also made it very clear that the Algonquin Negotiation Representative election process was run completely independently of the Algonquin National Tribal Council.

We signed a protocol last July with the Pikwakanagan First Nation establishing the independent process, and have been hands off ever since. I received the same notification as my opponent did, Davis said.

As recently as last spring, Chief Negotiator Robert Potts was saying that the Algonquin National Tribal Council elections, which were to take place in the fall of 2004, would result in democratically elected chiefs that could then represent their communities to the land claims process. After several divisive meetings, Mr. Potts had a change of heart and decided an independent process was necessary.

When contacted this week, Robert Potts said the process that was set up has been successfully carried out. Our first objective was to establish a list of electors that was not suspect in any way. To do that we engaged Joan Holmes, who has impeccable credentials as a genealogical researcher, and she has done a thorough and complete job.

Our second objective was to have an election that wouldnt preclude anyone from voting, or running in it. We have done that as well, with the hard work of Robert Johnson, who has acted as the electoral officer, Potts said.

While he acknowledged some of the timelines were tight, Potts said the process was fair.

We did have a problem with the time it takes for mail to be delivered, which is why we sent everything out from Ottawa instead of Toronto, and it is true the ballots arrived before the candidates biographical material. But very few ballots came back before the biographical material went out, we had a very good all-candidates meeting in Sharbot Lake, and a good turnout on April 25 at the polling station that was set up. I think we made an honest effort to ensure that the ballots reached the right people in time, he said.

As to the short time for an appeal, and charging a $200 fee, which pales against the high cost of the process as a whole, Robert Potts said, We want to get on with negotiations, and I think anyone who is seriously thinking about an appeal will be considering that long before the ballots are counted on May 7. The $200 fee is an attempt to recover some of the costs of the appeal.

Ardoch Algonquins

One of the reasons the Algonquin Negotiation Representative process was undertaken was to deal with the competing claims to the name of Ardoch Algonquin by two groups. This precipitated a dispute over membership lists. By setting up a new enrolment process, Robert Potts attempted to bypass the whole problem. People could affiliate themselves with Ardoch and vote for whomever they pleased without regard to who they considered to be the chief of the Ardoch Alghonquins.

In the end, the Ardoch Algonquin First Nation (AAFNA), under honorary Chief Harold Perry, the original Algonquin first Nation in Frontenac County and one of three off reserve groups that were involved in the land claims process when it started back in 1992, decided to opt out of the Algonquin Negotiation Representative process.

Their decision was explained in an ad that ran in this newspaper last week on page 6. In that ad they charge that the The group known as the Algonquin National Tribal Council is the only non-status group to have political access to the Algonquin Negotiation Representation Process. Through their lawyer they have constructed a process that ensures their leaders will be the elected representatives.

As well, AAFNA argues that they have been excluded by the Algonquin National Tribal Council, the Pikwakanagan reserve, and Ontario because AAFNA maintains a traditional governance structure.

The preference AAFNA chooses is to hold off on negotiating a treaty until the Algonquin people are in a stronger position. Their ad concluded, Although there are serious problems among Algonquin people, at no time in the past hundred years have so many people taken pride in their heritage and recognised their sacred responsibility to the Algonquin homeland. Algonquins are on a healing path. Just think what kind of treaty will be made when we are whole again.

The boycott of the Algonquin Negotiation Representative process by the Harold Perry group left Randy Malcolm, the Chief of the Ardoch Algonquin first Nation that is recognised by the Algonquin National Tribal Council, as the sole candidate for Negotiation Representative from Ardoch, and he was acclaimed to the position.

The position taken by Harold Perry and AAFNA is echoed throughout the Algonquin Nation, but others have decided to stay in the process rather than stand aside.

Heather Majaury, who is affiliated with the Sharbot Lake Algonquins, and was involved in the establishment of the Algonquin National Tribal Council but has become a sharp critic of the organization, said I publicly do not endorse the [Algonquin Negotiation Representative Process] and feel the way it was carried out was really problematic, but still I voted. I didnt walk away.

Lynn Gehl, a doctoral candidate in the Native Studies Department of Trent University, and an affiliate of the Greater Golden Lake Algonquins is a contestant in the election that is being held in her home community, greater Golden Lake against two other candidates, one of whom is her own brother.

She has similar concerns about how he election has ben run as Melinda Turcotte of Sharbot Lake does., The election process has undermined the efforts of new people coming in, she said, but she still feels her chances of being elected are excellent, even though her brother, Patrick Glassford, is the Algonuin National Tribal Council chief in greater Golden Lake.

If we have good, qualified leaders, were probably going to get a better deal, she said.