Jeff Green | Sep 16, 2015

Rightly so, Frontenac Park is considered the hidden jewel of Frontenac County. It is located in the midst of an array of communities and cottage lakes, within a stone's throw of Sydenham and is a short drive from Kingston; and yet it is a backwoods park in a unique geological and climactic location. It features the best canoeing, camping and hiking this side of Bon Echo Park, which is also a jewel but one that is less hidden and is also shared between Frontenac and Lennox and Addington.

In his definitive book on the back story about the land where Frontenac Park is located, “Their Enduring Spirit: the History of Frontenac Park 1783-1990”, Christian Barber extensively researched all of the development that took place in and around the park before the idea of a park was floated and eventually acted upon in the 1960s.

In doing so, Their Enduring Spirit is not only a valuable resource in terms of how the park was developed; it is also an account of the difficulties posed by the Frontenac Spur of the Canadian Shield on those who were unlucky enough to attempt homesteading in its rocky terrain.

The park is located in what were then Loughborough and Bedford Townships, now both part of the Municipality of South Frontenac. Many of the settlers who attempted to make a life in that region did so in the mid-to-late 1800s. There were some Loyalists among them, but there were also a number of Irish immigrants who made their way first to St. Patrick's Church in Railton, and then headed into the wilderness north of Sydenham in search of a new life.

What greeted them was brutal and difficult.

The history of a number of homesteading families forms the core of Their Enduring Spirit. Based on historic records, interviews with descendants who lived on or visited those who lived on the farms, and by walking the land and examining the remnants that are being reclaimed as wilderness lands, a picture of life in the back townships during the first 100 years of Frontenac County emerges.

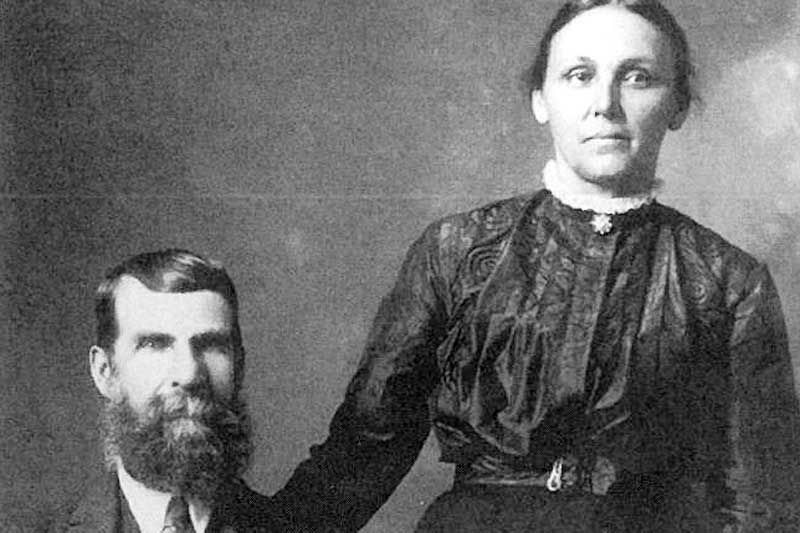

The first family to be profiled in the book is the Kemp family, who arrived at their farm at Otter Lake, near the west gate of the park, sometime in the 1860s. By the time of the 1871 census, William and Jane Kemp, both 47, had six children living with them. The land they laid claim to, in addition to other properties taken on by their son George, was very good by local standards. Over two decades of work, making use of the efforts of the entire family, 30 acres of the 95 acre property had been cleared.

“That might not sound like much to show for 20 years of labour, but in that district most farms worked 15 or 20 cleared acres. In fact the clearing was usually completed in relatively short order. But it was back-breaking work, without mechanical means. It involved cutting down the trees and clearing the brush, then burning the stumps that could not be wrenched from the ground by a team of horses or oxen and hauled away to form a first fence row. In the meantime the job of raising a crop to feed the family over the winter had to go on, and the first seeds were usually sown among the stumps ... it was no wonder that among the first settlers it was axiomatic to hate trees,” wrote Christian Barber in Their Enduring Spirit.

The Kemp family prospered, and by 1900 the original log cabin that was built in the early 1870s had disappeared beneath white, painted clapboard, and numerous outbuildings had been constructed as well. There was a root cellar below, and fields that extended right to the front doorway.

Still, cash was not easy to come by.

A ledger from M.A. Hogan's General Store in Sydenham illustrates this. In late 1912, Mary Shales Kemp, George's wife, who managed the family finances among numerous other tasks, purchased dishes, a pair of overalls for a dollar, and the indulgences of walnuts and a vase, for a total cost of $7.32.

Her custom was to pay for her purchases with butter and eggs from the farm. However on this occasion, after the eggs and butter were factored in there was a shortfall of $1.45. Back went the overalls and the extra 45 cents was paid in cash.

During the mica mining year in the first decade of the 20th century, George Kemp found a number of small deposits on his farm, and even took on investors to pay the $70 that was needed for drills and blasting powder at one site. However, enough mica was never found to make a profit on the venture.

To the extent that there were roads in the area, they were built and maintained by all of the farmers living in there, sometimes as part of their taxation responsibilities, which, in the late 19th century, included putting in some time improving the local roads.

While the Kemp family were able to establish a successful farm in what is now Frontenac Park, it was ultimately unsustainable. Mary Kemp lived on the farm after George died, but moved away in 1928 and sold the property in 1941. The last people to occupy it were a family from Wyoming in the late 1940s.

By the time Mary Kemp died in Sydenham in 1952 at the age of 93, the property where she had made her life had been abandoned and the house and barns had burned down.

When Christian Barber went to the property in the late 1980s as he was preparing his book, it was mostly overgrown with vegetation, and it required effort on his part to find the remnants of what had been a going concern for 60 or 70 years.

He notes this at the end of his chapter on the Kemp family of Kemp Road : “... the fields, so painstakingly cleared and planted and harvested by generations of settlers, are overgrown with sumac and birch, locust and juniper. Rusted barbed wire – embedded by years in the centre of the trees that it was originally stapled to the bark of – is stretched to the breaking point by fallen trees, and there is no one to cut them away; no farmer in overalls, with strong, knuckly, barked, and sun-tanned hands to walk the line on a summer day between haying and harvest and maintain a fence.”

The Kemp family's story is similar in outcome to others told in the book - struggle and some success followed by a move to better farmland elsewhere in the region or to work off the farm in Sydenham or beyond. Mining and logging were also prevalent in the park. Logging started in the early 19th century and mining later on, with the logging having the greatest impact on the land, as it did elsewhere in the region generally.

In the interesting chapter on mining, Barber touches on the story of Antoine Point on Devil Lake.

Francis Edward Antoine and his wife, Letitia Whiteduck, built a log cabin on the Point in the mid 19th century and they are buried there. One of their sons, John Antoine, is listed, along with the government, as the owner of Antoine Point in the 1883 Meacham map, one of the best source materials for information about land ownership in those years. John, with his wife Elizabeth Hollywood, had 11 children. According to Antoine family lore, it was John who found mica deposits at Antoine Point, although there are competing accounts about who found the ore at that location, and it seems that the Point became of interest to mining interests in the early 1890s.

There is an entry in the land registry indicating that John Antoine sold his interest in the land to William Jones for $50 in 1897, and the Antoines moved to Godfrey, and eventually back to Sharbot Lake, where another branch of the family was already located.

The idea of establishing a wilderness park on the lands in Loughborough and Bedford township that had resisted settlement, and whose lakes (Devil, Big Clear, Otter, and Buck) were not already cut up into cottage lots, was first floated in the 1940s.

In 1954 a Parks Division was created within the Department of Lands and Forests of Ontario (the precursor to the Ministry of Natural Resources.

In 1957, the Kingston Rod and Gun Club submitted a proposal for a new park to serve the growing numbers of people in Kingston and southern Frontenac County wanting to experience the great outdoors, hiking, camping, fishing and the enjoyment of a sandy beach.

The proposal included twenty seven 200 acre lots in Bedford and twenty five 200 acre lots in Lougborough, a total of 16.2 square miles, with an option to increase it to 23.7 square miles if the area below Otter lake was added.

That effort was not successful, and seemed to be dead when Murphy's Point Park on Big Rideau Lake near Perth was established instead.

Five years later, in 1962, another group, the Kingston Nature Club, put forward a similar proposal. This time, even though the cost of purchasing private land for the park had ballooned to $200,000, the proposal was successful. It eventually cost over $1 million to create Frontenac Park, which opened in the late 1960s.

The park's first superintendent, Bruce Page, was the great grandson of Jeremiah, one of the first settlers on the land in the vicinity of what became Frontenac Park.

More Stories

- Province clarifies stance - Says Private Well Water Testing Will Continue

- Frontenac County Stays Internal for CAO - Appoints Kevin Farrell

- Addington Highlands Tax Bill Going Up 6.93%

- Perth Road United Church Donation to The Grace Centre

- 21 Years Of Dump Life Left At South Frontenac Waste Site

- Eclipse 2024 – Once In A Lifetime

- National Tourism Week

- NeLL Spring Open House and Anniversary Concert

- 25 years at Bishop Lake Outdoor Centre

- Grounds Contracts Down, Custodial Contracts Up In Central Frontenac